05/11/2025

Abstract

Marine shrimp farming plays a vital role in Vietnam’s economy but is increasingly threatened by environmental change and climate variability. Vinh Long province, formerly Ben Tre, was selected as the study site because it is both a major shrimp farming hub and one of the regions most severely affected by salinity intrusion, drought, and extreme weather. These conditions make it representative for examining sustainability challenges in aquaculture. This study aims to assess the current status of shrimp farming, identify key factors influencing its sustainability, and propose solutions that integrate environmental and economic perspectives. A mixed-method approach was applied, combining secondary data from local reports with primary surveys of 52 farming households in Binh Dai, Ba Tri, and Thanh Phu districts. The Sustainable Livelihood Framework (DFID) and the Livelihood Capitals Index (LCI) were employed, with normalized indicators and radar charts used to compare strengths and vulnerabilities. Findings reveal that financial and social capitals are the strongest supports, while human and natural capitals remain the main constraints. The study proposes targeted training, adaptive water infrastructure, expanded credit access, and strengthened farmer organizations to enhance resilience. The results provide evidence for sustainable aquaculture policies in Vinh Long and the wider Mekong Delta.

Keywords: Aquaculture technology, climate change, policy support, shrimp farming, sustainable development.

JEL Classification: Q22, Q54, Q56, O13.

Received: 25th August 2025; Revised: 15th September 2025; Accepted: 22nd September 2025.

1. INTRODUCTION

Vietnam’s fisheries sector, particularly marine shrimp farming, continues to play a pivotal role in the national economy. According to the General Statistics Office and the Vietnam Association of Seafood Exporters and Producers, by 2022 the country’s aquaculture production reached 4.6 million tons, and seafood exports attained a historic milestone of USD 11 billion, with shrimp remaining the leading contributor to export value. The fisheries sector as a whole accounts for approximately 4–5% of Vietnam’s GDP and provides livelihoods for millions of rural and coastal households (Van Quang et al., 2023).

However, the rapid development of aquaculture has been increasingly threatened by climate change and environmental degradation. Vietnam is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change, facing rising sea levels, salinity intrusion, droughts, and extreme weather events(Tuyet Hanh et al., 2020). The Mekong Delta, which produces more than 60% of Vietnam’s farmed shrimp, is particularly exposed, with large areas experiencing saline intrusion during the dry season and flooding in the wet season. These phenomena have directly reduced water quality, lowered shrimp yields, and increased production risks (Bhowmik et al., 2023).

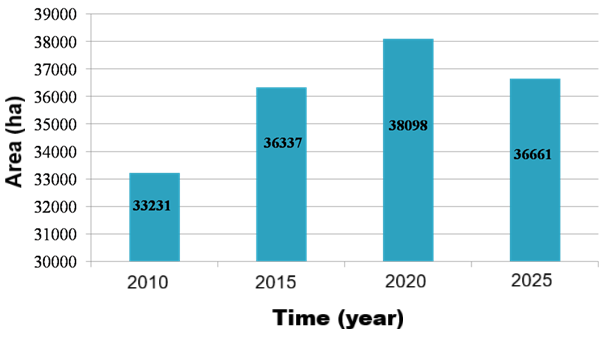

Within this context, Vinh Long province (formerly Ben Tre) represents a critical case. This region has long been a major shrimp farming hub, with approximately 36,661 ha of ponds in 2025, accounting for more than 80% of its aquaculture area. Yet production has not kept pace with expansion, peaking at 55,946 tons in 2015 before declining to 45,479 tons in 2025, largely due to environmental stress, disease outbreaks, and seed quality constraints (Nguyen et al., 2021). Ben Tre (now incorporated into Vinh Long) was chosen as the research site not only because of its significant shrimp farming area and contribution to the Mekong Delta economy, but also because it is one of the provinces most severely affected by salinity intrusion, drought, and climate variability(Tran, Thuan, et al., 2025). These conditions make it a representative and urgent case for analyzing the sustainability of shrimp aquaculture.

Sustainable development in fisheries must go beyond increasing output to ensure environmental protection and improvements in community livelihoods. As defined by the Food and Agriculture Organization (Hamilton, 2019), sustainable aquaculture involves managing natural resources rationally to meet human needs without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their own. Studies on shrimp farming in Vietnam have identified key sustainability constraints (Engle et al., 2017), including overuse of antibiotics and chemicals, environmental pollution, and inadequate infrastructure. Research in Vinh Long has further highlighted that while shrimp farming areas continue to expand, productivity remains unstable due to climate impacts and disease risks (Tran, Duong, et al., 2025).

Although previous studies have addressed the economic and environmental aspects of shrimp farming, few have systematically examined the combined role of environmental change, economic development policies, and technological adoption in shaping sustainability pathways. Moreover, integrated frameworks that assess the interaction between livelihood capitals and policy support remain limited in the Mekong Delta context

The objective of this research is therefore threefold: (i) to analyze the current status of marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long (formerly Ben Tre); (ii) to assess the key factors influencing sustainability, with particular emphasis on the impacts of climate variability and livelihood capital vulnerabilities; and (iii) to propose policy-relevant solutions that integrate environmental resilience, technological innovation, and economic development. The novelty of this study lies in its application of the Livelihood Capitals Index (LCI) and radar chart analysis to comprehensively evaluate sustainability across multiple dimensions. Its significance extends beyond Vinh Long, offering evidence-based insights for designing resilient shrimp farming models in the Mekong Delta and informing national strategies for sustainable aquaculture development.

2. METHODOLOGY

2.1. Research area

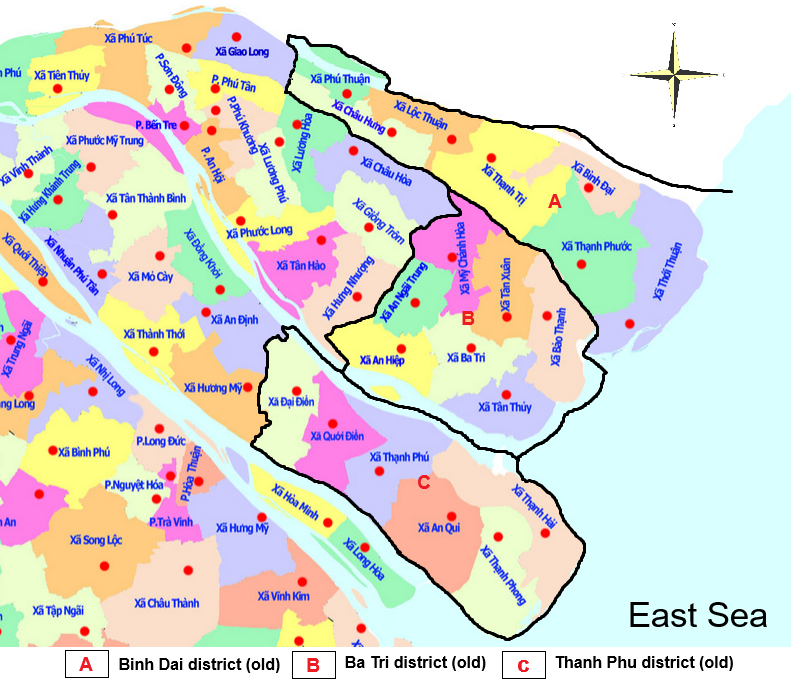

This study was carried out in the coastal districts of the former Ben Tre province(Nguyen et al., 2021), namely Binh Dai, Ba Tri, and Thanh Phu, which were the major centers of marine shrimp farming in the Mekong Delta. These districts were administratively merged into the newly established Vinh Long province in July 2025, following Resolution No. 1687/NQ-UBTVQH15 on the reorganization of commune-level administrative units in Vinh Long province. Although now part of Vinh Long, the geographical and ecological conditions of these areas remain those of the former Ben Tre, characterized by extensive wetlands, coastal ecosystems, and large shrimp farming zones.

Figure 1. Research area with Binh Dai, Ba Tri, and Thanh Phu districts (former) on the new map of Vinh Long province (after the 2025 merger).

The field survey specifically targeted shrimp farming households in these three coastal districts prior to the administrative merger. A total of 52 structured questionnaires were collected, distributed as follows: 16 from Binh Dai, 21 from Ba Tri, and 15 from Thanh Phu. These districts were chosen as the research focal points due to their significant shrimp farming areas, their exposure to critical challenges such as climate change and salinity intrusion, and their continuous growth in aquaculture activities over recent years. Such characteristics provided a robust basis for assessing environmental, social, and economic factors influencing the sustainable development of the shrimp farming sector in the region.

2.2. Data collection

2.2.1.Questionnaire Content Based on the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (DFID)

The household survey was developed on the basis of the Sustainable Livelihood Framework (SLF) proposed by DFID (1999), which emphasizes the interactions among five key livelihood capitals: human, social, physical, financial, and natural. The questionnaire was structured to operationalize these capitals in the context of marine shrimp farming, capturing both socioeconomic and environmental dimensions that influence sustainable development.

Human capital: number and education of main laborers engaged in shrimp farming; ratio of active laborers to household members; highest educational attainment of family members.

Social capital: household perceptions of local infrastructure (electricity, transportation, irrigation, education, healthcare); participation in local organizations (farmer associations, aquaculture cooperatives, women’s unions); frequency of training or extension workshops; and shrimp marketing channels.

Physical capital: household economic conditions reflected in housing and living standards; changes in aquaculture land over the past five years; ownership of aquaculture equipment and communication technologies (internet access).

Financial capital: household investment in shrimp farming; net income from aquaculture after deducting costs; main production model (type, scale, yield per hectare); monthly expenditures; and household financial capacity to sustain farming under environmental stress.

Natural capital: perceived impacts of drought, salinity intrusion, flooding, prolonged heat, and heavy rainfall on shrimp farming, assessed on a five-point scale from “no impact” to “very severe impact.”

By aligning the survey content with the DFID framework, this study systematically integrates both policy-relevant socioeconomic aspects and environmental challenges into the assessment of sustainable shrimp farming in Vinh Long

2.2.2. Livelihood Capitals Index (LCI)

The calculation of LCI followed the balanced weighted-average approach proposed by Sullivan et al. (2002). In this method, each sub-component contributes equally to the overall index, regardless of differences in the number of sub-components under each major component. The methodology is adapted from Hahn et al. (2009), with modifications to fit the local context. Since each indicator was measured on different scales, all sub-components were normalized into a comparable index using the following equation (1):

(1)

where Sr represents the original value of a sub-component in the study area, while Smin and Smax are the minimum and maximum values, respectively.

After normalization, the sub-components were averaged to calculate the value of each major component (Mri) using equation (2):

(2)

where Indexsri denotes the indexed values of the sub-components, and nnn is the number of sub-components in each major component.

Finally, the composite Livelihood Capitals Index (LCIr) was calculated as in equation (3):

(3)

where WMi is the weight of each major component, defined as the number of sub-components that constitute it, following the balanced weighting principle of Sullivan et al. (2002).

This methodological framework enables an integrated evaluation of how environmental, social, and economic dimensions jointly influence the sustainability of shrimp farming households. By applying both LCI and radar chart visualization, the study provides a comparative assessment of the vulnerabilities and strengths across the surveyed communes, thereby informing strategies to align environmental resilience with economic development policies for sustainable aquaculture in Vinh Long.

2.3. Data Analysis Methods

This study draws upon both primary and secondary data sources to analyze the sustainable development of marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long. The analytical framework integrates the Livelihood Capitals Index (LCI) with Radar Chart visualization to assess the combined effects of five livelihood capitals and to compare the relative impacts across two surveyed communes.

Secondary data were collected from commune and district-level reports within the study area, providing background information on environmental, economic, and social conditions. Primary data were obtained through household surveys, in which information was recorded based on structured questionnaires targeting shrimp farming households. All collected data were systematically compiled, summarized, and analyzed using Microsoft Excel (version 2010).

The LCI framework evaluates sustainable livelihoods through five major components: (i) human capital, (ii) social capital, (iii) physical capital, (iv) financial capital, and (v) natural capital. Each major component is further divided into several sub-components, which were identified based on household surveys and interviews in the study area.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Assessment of the current status of marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long, former Ben Tre area

Marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long (formerly Ben Tre) has expanded significantly in recent years, making an important contribution to the fisheries sector of the Mekong Delta. According to the report of the Vinh Long Department of Agriculture and Rural Development, as shown in Figure 2, the marine shrimp farming area of the province reached approximately 36,661 ha in 2025, accounting for 81.2% of the total aquaculture area. Coastal districts such as Ba Tri, Binh Dai, and Thanh Phu represent the largest shrimp farming zones, contributing the bulk of the province’s output. While the farming area has steadily increased, production and productivity have not followed a consistent upward trend. In particular, production rose from 29,208 tons in 2010 to 55,946 tons in 2015, but then declined to 45,479 tons in 2025, reflecting the impacts of environmental stressors and other external factors.

Figure 2. Statistics on marine shrimp area in Ben Tre region of Vinh Long province.

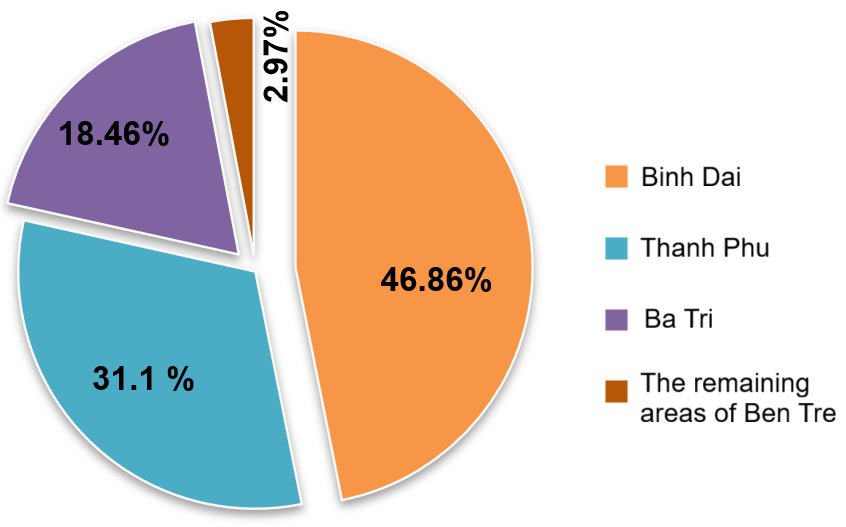

The structure in Figure 3 illustrates that shrimp output is highly concentrated in three coastal districts: Binh Dai accounts for 46.86%, Thanh Phu for 31.10%, and Ba Tri for 18.46%, while other areas contribute only 2.97%. Such spatial concentration implies that risks of disease transmission and environmental disturbances are particularly severe in these districts, highlighting the need for prioritized investment in irrigation, electricity supply, and disease management, as shown in Figure 2. One of the main factors affecting the sector is climate change, particularly salinity intrusion(Bhowmik et al., 2023). The coastal districts with large shrimp farming areas frequently face saline intrusion during the dry season. Prolonged droughts and abnormal weather patterns have further reduced freshwater availability, making water supply for shrimp ponds increasingly difficult. Salinity intrusion not only reduces shrimp yield but also degrades shrimp quality by creating unsuitable water conditions. In practice, many farmers in salinity-affected areas have reported mass shrimp mortalities due to substandard water quality.

Beyond environmental issues, disease outbreaks remain one of the most serious challenges for marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long. Diseases such as white spot syndrome and acute hepatopancreatic necrosis, caused by bacterial and viral agents, have resulted in significant production losses. Statistics indicate that mortality rates in previous production cycles reached 30–40%, reducing both productivity and efficiency. Although farmers have implemented preventive measures such as pond renovation, antibiotic use, and stricter water management, disease outbreaks continue to occur due to unstable pond environments and insufficiently effective disease control.

Seed quality is another crucial factor influencing productivity and product quality(Ngo et al., 2022). In Vinh Long, however, seed quality remains problematic. Most seed is supplied by hatcheries within the province and neighboring regions, but not all hatcheries meet high-quality standards. As a result, seed quality is inconsistent in size and growth performance, reducing the effectiveness of production cycles. Poor-quality seed often leads to higher mortality rates and slower growth, thereby diminishing final yields.

Figure 3. Structure of marine shrimp output by district and town in Ben Tre region (Vinh Long province).

Despite ongoing efforts to improve seed quality and adopt advanced farming technologies, the application of modern practices remains limited. High-tech models, such as lined ponds and two-stage farming, have been piloted in some areas of the province. These systems help increase productivity and reduce disease risks, but their initial investment costs are prohibitively high(Tran, Thuan, et al., 2025). Many smallholder farmers cannot adopt such systems due to limited access to capital. Credit support and loan programs remain insufficient, restricting the wider diffusion of these advanced models.

Infrastructure for shrimp farming in Vinh Long also remains inadequate. Although improvements have been made in recent years, many coastal areas still lack effective water supply and drainage systems. This deficiency makes it difficult to maintain water quality in ponds, especially during the dry season when freshwater is scarce. In addition, challenges in waste treatment and pollution from shrimp farming activities need to be addressed to protect the environment and sustain the long-term development of the sector.

Overall, marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long continues to face significant challenges, particularly with respect to environmental pressures, seed quality, and disease outbreaks. Nonetheless, with improved infrastructure, the adoption of new technologies, and the development of sustainable farming models, shrimp farming can continue to grow and make a positive contribution to the provincial economy. Coordinated solutions are required to overcome current limitations, alongside enhanced application of science, technology, and supportive policies to raise productivity and efficiency in the sector.

3.2. Factors affecting the sustainable development of marine shrimp farming

3.2.1. Livelihood capital assessment across districts

The analysis of the Livelihood Capitals Index (LCI) highlights both strengths and weaknesses in the shrimp farming households across the three surveyed districts of the former Ben Tre province, now part of Vinh Long.

Table 1.Values of the main components of the LCI index in Binh Dai district

|

Key elements |

LCI index |

Key components |

LCI index |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Binh Daidistrict |

Binh Daidistrict |

||

|

Human capital |

0.511 |

Knowledge and skills |

0.722 |

|

Experience and labor resources |

0.3005 |

||

|

Social capital |

0.572 |

Demographics |

0.547 |

|

Social networks |

0.597 |

||

|

Physical capital |

0.59 |

Housing, land, and infrastructure |

0.59 |

|

Financial capital |

0.68 |

Finance and income |

0.68 |

|

Natural capital |

0.5 |

Natural resources |

0.5 |

|

Climate |

0.5 |

In Binh Dai district, the LCI results indicate that financial capital (0.68) was the most favorable component, reflecting relatively strong household income and financial resources to sustain aquaculture. Social capital (0.572) and physical capital (0.59) also reached moderate levels, suggesting adequate social networks and infrastructure. However, human capital (0.511) and especially the sub-component of labor experience and availability (0.3005) were comparatively weak, while natural capital was the lowest at 0.50, revealing vulnerabilities to environmental stresses (Table 1).

Table 2.Values of the main components of the LCI index in Ba Tri district

|

Key elements |

LCI index |

Key components |

LCI index |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Ba Tridistrict |

Ba Tridistrict |

||

|

Human capital |

0.46 |

Knowledge and skills |

0.48 |

|

Experience and labor resources |

0.44 |

||

|

Social capital |

0.65 |

Demographics |

0.53 |

|

Social networks |

0.77 |

||

|

Physical capital |

0.505 |

Housing, land, and infrastructure |

0.505 |

|

Financial capital |

0.603 |

Finance and income |

0.603 |

|

Natural capital |

0.526 |

Natural resources |

0.5 |

|

Climate |

0.553 |

In Ba Tri district, the pattern differed somewhat. Here, social capital was highest at 0.65, indicating strong household participation in local organizations and satisfaction with infrastructure, particularly the sub-component of social networks (0.77). Financial capital (0.603) also played a critical role in supporting shrimp farming households. By contrast, human capital was lowest at 0.46, with relatively low scores in both knowledge/skills (0.48) and labor resources (0.44). Natural capital scored 0.526, reflecting moderate exposure to salinity intrusion and climatic variability, while physical capital was also relatively weak (0.505) (Table 2).

Table 3. Values of the main components of the LCI index in Binh Dai district

|

Key elements |

LCI index |

Key components |

LCI index |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Thanh Phudistrict |

Thanh Phudistrict |

||

|

Human capital |

0.544 |

Knowledge and skills |

0.75 |

|

Experience and labor resources |

0.338 |

||

|

Social capital |

0.657 |

Demographics |

0.674 |

|

Social networks |

0.641 |

||

|

Physical capital |

0.529 |

Housing, land, and infrastructure |

0.529 |

|

Financial capital |

0.66 |

Finance and income |

0.66 |

|

Natural capital |

0.554 |

Natural resources |

0.5 |

|

Climate |

0.608 |

In Thanh Phu district, the LCI profile revealed a more balanced situation. Financial capital remained strong at 0.66, supported by social capital (0.657), which highlighted the role of community participation and demographic structure. Human capital reached 0.544, slightly higher than Ba Tri, largely due to strong knowledge and skills (0.75), though labor resources were again limited (0.338). Natural capital showed improvements with a score of 0.554, driven by better adaptation to climatic conditions (0.608), while physical capital was somewhat modest at 0.529 (Table 3).

Overall, these findings suggest that financial and social capitals consistently emerged as the most supportive factors for sustainable shrimp farming across all three districts. In contrast, human capital and natural capital represent the main constraints, particularly the shortage of skilled labor, dependence on family workforce, and vulnerability to environmental stressors such as drought, salinity intrusion, and flooding. The results highlight the need for policies that strengthen human capital (e.g., training, extension services) and enhance environmental resilience (e.g., adaptive infrastructure, water resource management) to ensure the long-term sustainability of marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long.

3.2.2.Comparative analysis of strengths and vulnerabilities

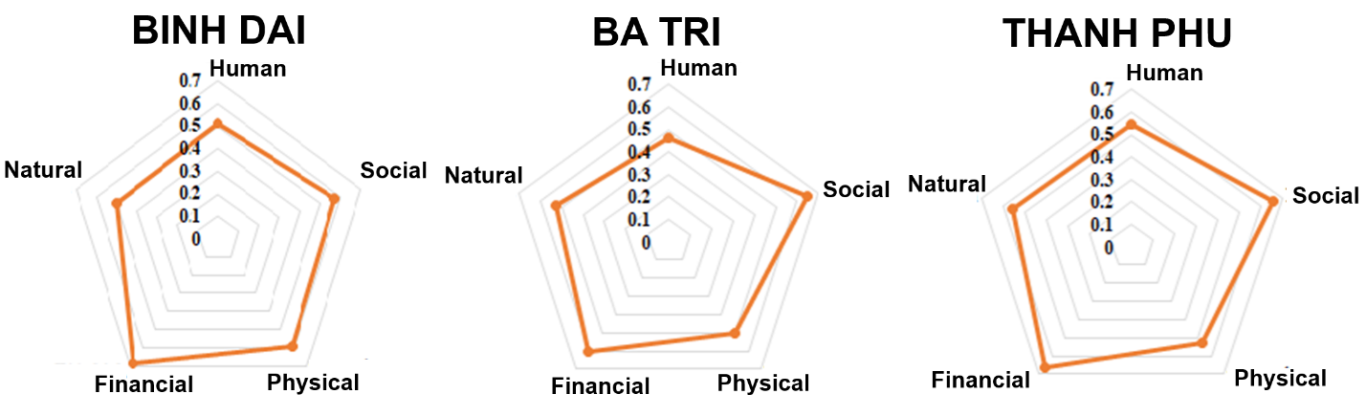

The radar charts in Figure 4 illustrate the relative strengths and weaknesses of the five livelihood capitals across the three districts. A consistent pattern emerges in which financial and social capitals are the strongest dimensions in all districts, particularly in Ba Tri and Thanh Phu, where social capital exceeds 0.65. These results reflect the importance of household income and the role of social networks, organizations, and infrastructure in supporting shrimp farming.

Figure 4. Radar chart of livelihood capitals (LCI) for marine shrimp farming households in Binh Dai, Ba Tri, and Thanh Phu districts.

By contrast, human capital and natural capital appear to be the most constrained factors. Human capital remains below 0.55 in all districts, with the lowest in Ba Tri (0.46), indicating limited skills, education, and labor resources available for shrimp aquaculture. Natural capital also shows vulnerability, with Binh Dai scoring the lowest at 0.50, highlighting exposure to salinity intrusion, climatic variability, and resource depletion. Physical capital is relatively moderate across the three districts, fluctuating between 0.50 and 0.59, suggesting an ongoing need for improved infrastructure and farming facilities.

The comparative profile shows that while Binh Dai faces the greatest vulnerability in natural and human capitals, Ba Tri performs better in social networks but remains weak in physical conditions, and Thanh Phu presents a relatively balanced but still constrained profile in human and natural aspects. These variations point to the need for location-specific strategies that address both socio-economic and environmental challenges.

3.3. Proposed solutions for the sustainable development of marine shrimp farming

Based on the LCI analysis, several policy and management solutions can be proposed to enhance the sustainability of marine shrimp farming in Vinh Long:

Strengthening human capital, training and capacity-building programs should be prioritized to improve farmers’ technical knowledge and aquaculture management skills. Extension services, farmer field schools, and collaboration with research institutions can help reduce the gap in human resources, particularly in Ba Tri where human capital is weakest.

Enhancing natural capital resilience, adaptive strategies are needed to mitigate the risks of climate change, salinity intrusion, and resource degradation. Investments in water management infrastructure, such as salinity control sluices and sustainable water reuse systems, can strengthen resilience. Ecological approaches, including mangrove-shrimp integrated systems and environmentally friendly farming practices, should be promoted.

Consolidating financial capital, access to credit and financial services should be expanded to support household investments in technology and adaptive practices. Policies that encourage cooperative models or collective financing can reduce risks and stabilize income for small-scale farmers.

Upgrading physical capital, infrastructure improvements, such as reliable electricity, roads, and cold-chain facilities, are essential to reduce post-harvest losses and improve market access. Adoption of digital monitoring systems (IoT, water quality sensors) should also be supported to optimize farming operations.

Leveraging social capital, the strength of community networks in Ba Tri and Thanh Phu suggests that local organizations and cooperatives can serve as effective platforms for knowledge exchange, collective action, and sustainable certification programs (e.g., ASC, VietGAP). Encouraging wider farmer participation in associations will enhance resilience and bargaining power in the market.

In summary, while financial and social resources currently underpin the viability of shrimp farming, the long-term sustainability of the sector requires significant investments in human capital development and environmental resilience. Tailored solutions at the district level – focusing on the weakest livelihood dimensions – will be critical for ensuring sustainable development under changing ecological and socio-economic conditions.

4. CONCLUSION

The findings highlight that financial and social capitals currently provide the strongest support for farming households, while human and natural capitals remain the most critical constraints. Specifically, labor resources, skills, and environmental vulnerability to salinity intrusion and climate variability continue to undermine long-term sustainability.The novelty of this research lies in its integration of livelihood capital assessment with policy-oriented analysis, providing a multidimensional view of shrimp aquaculture that combines environmental resilience and economic development strategies. This approach offers practical implications for policymakers, particularly in designing adaptive infrastructure, expanding credit access, and strengthening farmer training and community-based organizations.

The study’s significance extends beyond Vinh Long, offering lessons for sustainable aquaculture in other climate-vulnerable regions of the Mekong Delta. Future research should focus on testing adaptive models that integrate technological innovation (e.g., IoT-based water management), ecological practices (e.g., mangrove–shrimp systems), and participatory governance, thereby strengthening both household resilience and sectoral sustainability under accelerating climate change.

Acknowledgment: This research was supported by Nguyen Tat Thanh University, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

Trần Thị Diễm Kiều,1

Trần Thành2,3,*

1University of Economics and Law (UEL), Vietnam National University Ho Chi Minh City (VNU-HCMC)

2Institute of Interdisciplinary Sciences (IIS), Nguyen Tat Thanh University, Ho Chi Minh City,

3Center for Hi-Tech Development, Nguyen Tat Thanh University, Saigon Hi-Tech Park, Ho Chi Minh City

(Source: The article was published on the Environment Magazine by English No. III/2025)

REFERENCES

1. Bhowmik, B. C., Rima, N. N., Gosh, K., Hossain, M. A., Murray, F. J., Little, D. C., & Mamun, A.-A. (2023). Salinity extrusion and resilience of coastal aquaculture to the climatic changes in the southwest region of Bangladesh. Heliyon, 9(3).

2. Engle, C. R., McNevin, A., Racine, P., Boyd, C. E., Paungkaew, D., Viriyatum, R., Tinh, H. Q., & Minh, H. N. (2017). Economics of sustainable intensification of aquaculture: evidence from shrimp farms in Vietnam and Thailand. Journal of the World Aquaculture Society, 48(2), 227-239.

3. Hamilton, S. E. (2019). Shrimp farming. In Mangroves and Aquaculture: A Five Decade Remote Sensing Analysis of Ecuador’s Estuarine Environments (pp. 41-67). Springer.

4. Ngo, T. T. D., Nguyen, T. C. T., Vo, T. T. P., Tran, L. K., Nguyen, T. H., Nguyen, D. T. N., Tran, D. D., & Dang, T. T. T. (2022). Factors affecting water quality and shrimp production in the mixed mangrove‐shrimp systems in the Mekong Delta of Vietnam. Aquaculture Research, 53(2), 497-517.

5. Nguyen, K. A. T., Nguyen, T. A. T., Bui, C. T., Jolly, C., & Nguelifack, B. M. (2021). Shrimp farmers risk management and demand for insurance in Ben Tre and Tra Vinh Provinces in Vietnam. Aquaculture Reports, 19, 100606.

6. Tran, T., Duong, D. V., Le, T. D., Loc, H. H., Chau, L. T. N., Le, L.-T., & Bui, X.-T. (2025). Promoting sustainable shrimp farming: balancing environmental goals, awareness, and socio-cultural factors in the Mekong Delta aquaculture. Aquaculture International, 33(2), 119.

7. Tran, T., Thuan, V. H., & Van Tan, L. (2025). Financial efficiency of farming models adapting to climate change in the Ben Tre area. In The Mekong Delta Environmental Research Guidebook (pp. 415-440). Elsevier.

8. Tuyet Hanh, T. T., Huong, L. T. T., Huong, N. T. L., Linh, T. N. Q., Quyen, N. H., Nhung, N. T. T., Ebi, K., Cuong, N. D., Van Nhu, H., & Kien, T. M. (2020). Vietnam climate change and health vulnerability and adaptation assessment, 2018. Environmental Health Insights, 14, 1178630220924658.

9. Van Quang, N., & Binh, T. T. (2023). Mariculture development in Vietnam: Present status and prospects. The VMOST Journal of Social Sciences and Humanities, 65(3), 11-20.