27/12/2024

Abstract

With an extensive coastline and abundant wind resources, Vietnam can achieve an offshore wind technical potential of nearly 600 GW, significantly contributing to ensuring energy security and reducing carbon emissions. Experience from leading countries such as the UK, Denmark, Germany, and China shows the need for strong and synchronous support policies and close coordination among stakeholders. The study analyzes the potential, opportunities, challenges and barriers in developing offshore wind power in Vietnam. These challenges and barriers need to be removed, such as the lack of a synchronous legal framework, inappropriate bidding mechanisms and electricity prices, unready technical infrastructure and supply chains, and limited domestic capacity in technology and human resources. On that basis, the authors propose 8 groups of solutions: completing the legal framework, establishing a focal management agency, promulgating incentive policies, investing in research and development of human resources, spatial planning for marine space, strengthening international cooperation, leveraging green financial resources and raising community awareness and engagement.

Key words: Offshore wind power, renewable energy, marine spatial planning, supply chain, international cooperation.

JEL Classifications: Q51, Q56, Q57.

Received: 31st July 2024; Revised: 10th August 2024; Accepted: 5th September 2024.

1. Introduction

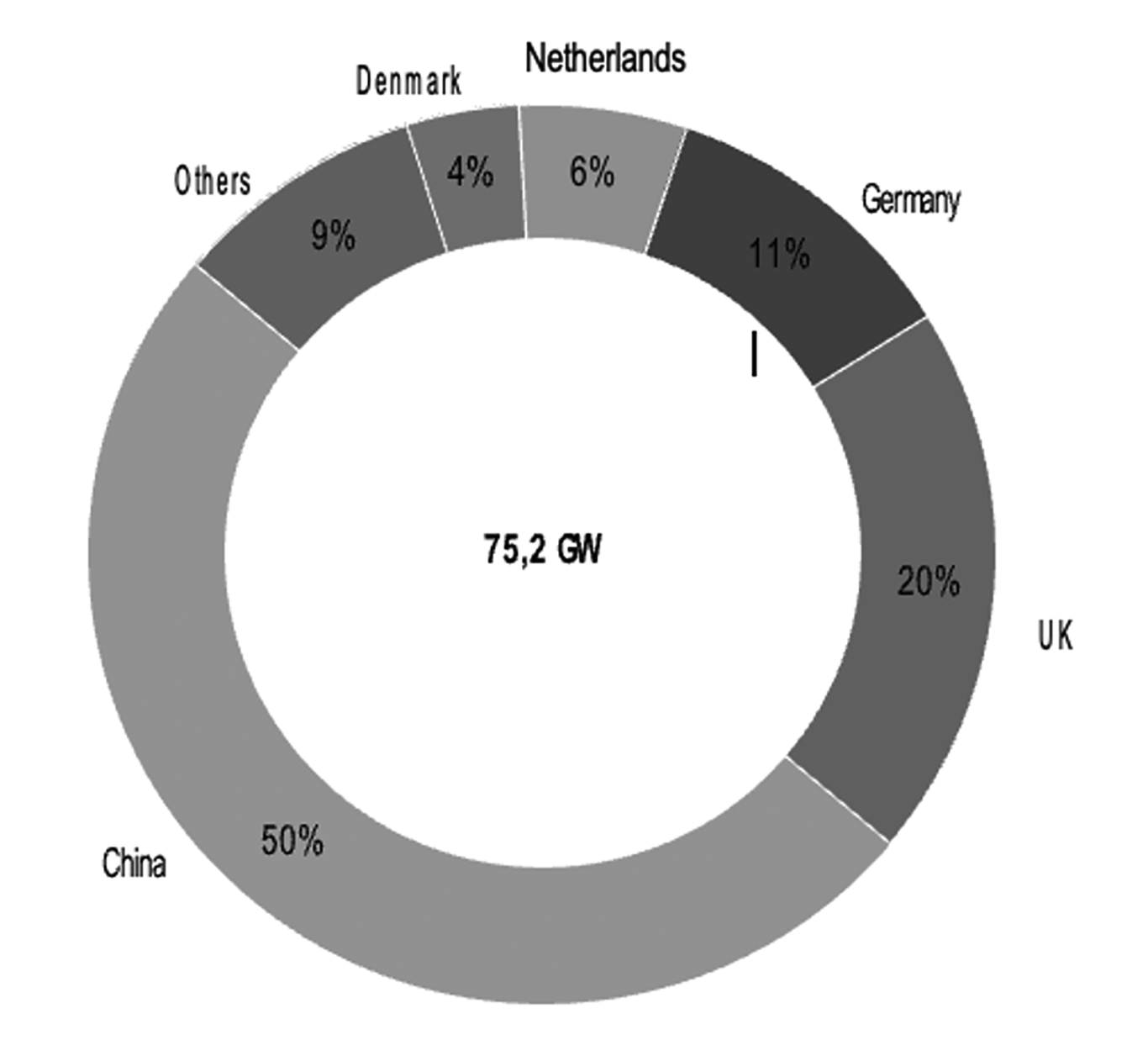

Offshore wind power has become a significant source of renewable energy globally over the past three decades. By the end of 2023, the total global installed capacity of offshore wind power reached 75.2 GW, an increase of nearly 17% compared to 2022 [1]. The leading countries in offshore wind power development today include China, the United Kingdom, Germany, the Netherlands, and Denmark. According to forecasts by the World Energy Council (WEC), by 2050, offshore wind power could meet about 10% of the world's electricity demand, with a total installed capacity of up to 1,000 GW [2].

Vietnam is considered a country with enormous potential for offshore wind power development, with a coastline of more than 3,260 km and average wind speeds of 7 - 11 m/s [3]. According to a survey by the World Bank, the technical potential of offshore wind power in Vietnam is nearly 600 GW, which is many times greater than the total capacity of the current national power system [4]. Offshore wind power will contribute to ensuring national energy security, reducing reliance on imported fuels, and fulfilling the government's commitment to net-zero emissions by 2050. Notably, developing offshore wind power also holds significant importance in affirming Vietnam's sovereignty and sovereign rights at sea.

Despite having great potential and favorable conditions for offshore wind power development, Vietnam is facing significant challenges, with the main barrier being the lack of mechanisms and policies. In addition, the absence of a comprehensive legal framework and national maritime spatial planning also hinders the implementation of offshore wind power projects. With its considerable advantages and opportunities, Vietnam needs to take firm steps to timely harness its offshore wind power potential to become a leading country in the renewable energy sector in Southeast Asia. A systematic and comprehensive strategy for offshore wind power development will lay the foundation for sustainable growth, enhance the competitiveness of the economy, and contribute positively to global climate change mitigation goals.

Figure 1. Share of offshore wind power in renewable energy sources, 2050 [5]

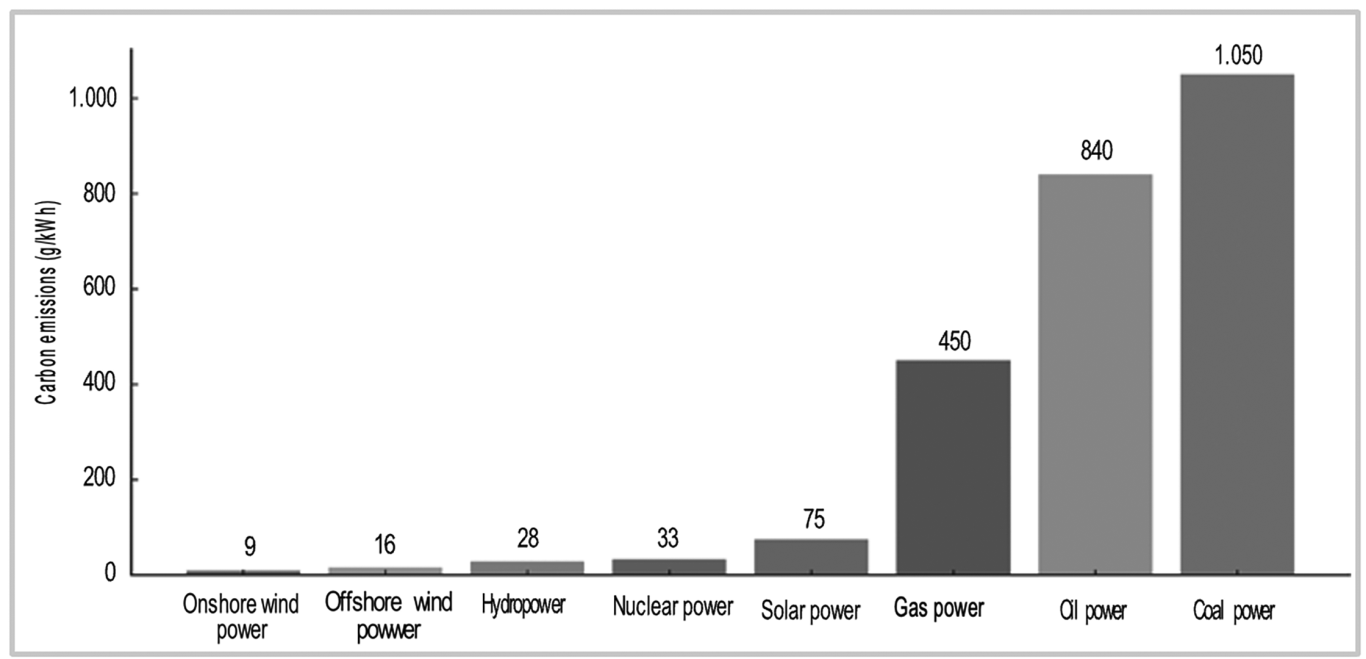

Figure 2. Carbon emissions per 1 kWh of electricity [5]

2. Offshore wind power and global development policies

The global trend to reduce greenhouse gas emissions to address climate change has created a demand for low-carbon renewable energy sources. According to the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA), renewable energy sources could generate 130,000 TWh of electricity annually, more than twice the current global electricity consumption [5]. By 2050, offshore wind power could account for nearly 40% of global renewable electricity generation (Figure 1).

Offshore wind power, along with onshore wind power, results in very low greenhouse gas emissions compared to current power sources, at around just over 10 g CO2/kWh, which is 1/100th of coal power (Figure 2).

The technology for converting wind at sea into electricity uses large wind turbines with capacities up to 16-20 MW, designed for longer lifespans of up to 25-30 years, with rapidly decreasing costs and suitable for harsh marine conditions. Offshore wind power harnesses wind energy at sea, converting it into electrical energy and supplying it to the onshore transmission grid. The world’s first offshore wind farm, Vinderby, with a capacity of 4.95 MW, located off Lolland, Denmark, was commissioned in 1991 and was officially decommissioned and dismantled in 2017 after 26 years of operation [6].

Figure 3. Total installed offshore wind power capacity by country as of the end of 2023 [1]

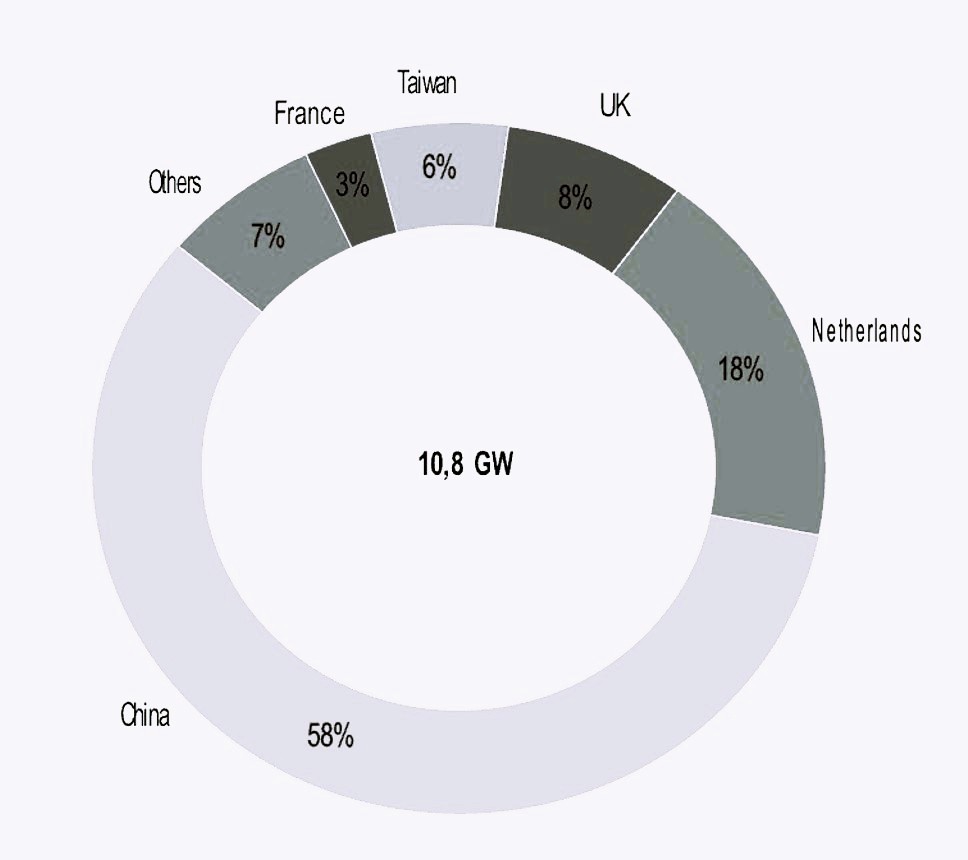

Figure 4. Total newly installed offshore wind power capacity in 2023 and its share by country [1]

Offshore wind power has been deployed on a large scale in China, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, and the United Kingdom. For many countries, offshore wind power has established itself as a large-scale, clean, and reliable electricity generation option, with suchadvantages as:

According to statistics from the Global Wind Energy Council (GWEC), by the end of 2023, the total installed offshore wind power capacity globally reached 75.2 GW. Leading the way are China (37.6 GW), accounting for 50%; the United Kingdom (13.6 GW), accounting for 20%; Germany (8 GW), accounting for 11%; the Netherlands (4.5 GW), accounting for 6%; and Denmark (3 GW), accounting for 4%. These five countries account for 91% of the total global offshore wind power capacity, while the remaining countries, including Vietnam, account for only 9% [1].

The total installed offshore wind power capacity is growing rapidly worldwide, reaching 15 GW in 2021, 10 GW in 2022, and nearly 11 GW in 2023. In 2023 alone, China accounted for 58% of the new global offshore wind power capacity, followed by the Netherlands at 18%, the United Kingdom at 8%, Taiwan at 6%, France at 3%, and other countries at 7% [1].

According to forecasts by the International Energy Agency (IEA), by 2040, $1 trillion will be invested in offshore wind power, with Asia accounting for over 60%. China's offshore wind power capacity has increased from 4 GW in 2019 to more than 37.6 GW (exceeding Europe's total offshore wind power capacity) and is projected to reach 110 GW by 2040 and 350 GW by 2050.

The renewable energy policies and laws of several countries, including China, Denmark, the United Kingdom, and Germany, are considered quite advanced and comprehensive. These countries have had renewable energy laws and have been promoting renewable energy development in general and offshore wind power specifically since the 2000s, achieving significant milestones. In 2021, Australia also introduced specific legislation for offshore wind power.

Particularly, Denmark plans to consume 50% of its electricity from offshore wind energy by 2030, while the United Kingdom has successfully established the largest offshore wind project in the world. However, implementing offshore wind projects also faces difficulties and challenges such as land ownership disputes, marine resource conflicts, and environmental protection issues. Therefore, cooperation between countries and international organizations is necessary to develop a suitable legal and policy framework for offshore wind development, while ensuring stakeholder interests and environmental protection.

Recently, countries with specific policies for offshore wind energy include dedicated licensing agencies such as the U.S. Bureau of Ocean Energy Management (BOEM) and Australia’s Department of Energy and Climate Change, along with various laws and strategies related to offshore wind development.

Leading countries in offshore wind development, such as Denmark, the United Kingdom, and Germany, have implemented effective support policies. Denmark, a pioneer, established the Offshore Wind Act in 1991, setting up a competitive bidding mechanism and financial support for projects [7]. The United Kingdom introduced the Energy Act in 2013 with specific targets for offshore wind and a price support mechanism (CfD) [8]. Germany enacted the Renewable Energy Act (EEG) with a feed-in tariff for offshore wind power starting in 2000 [9].

These countries have also facilitated maritime spatial planning, investment in grid infrastructure, supply chains, and logistics. Denmark has developed a wind atlas, planned potential areas, and infrastructure connectivity. The United Kingdom has established project zones and invested in upgrading transmission grids. Germany has created integrated planning for offshore wind farms [10].

In terms of technology, these countries focus on investing in research and developing advanced solutions such as large-capacity turbines (10-15 MW), floating foundations for deep waters, and energy storage systems [11]. State incentives and funding have encouraged the involvement of research institutes, universities, and collaboration with leading turbine manufacturers such as Vestas, Siemens Gamesa, and GE.

However, expanding offshore wind capacity also poses significant challenges. Issues such as high initial investment costs, complex licensing processes, and conflicts with stakeholders (e.g., fishermen, maritime transport) are major barriers [12]. Integrating a large amount of offshore wind power into the electricity system also requires substantial upgrades to grid infrastructure, increased reserve capacity, and flexibility of other power sources. Additionally, environmental impacts such as noise and changes in marine ecosystems need to be monitored and mitigated [13].

To overcome these challenges, improving the legal framework, attracting private investment, and enhancing regional and international cooperation are considered key solutions. The experiences of leading countries will provide valuable lessons for Vietnam in its future offshore wind power development.

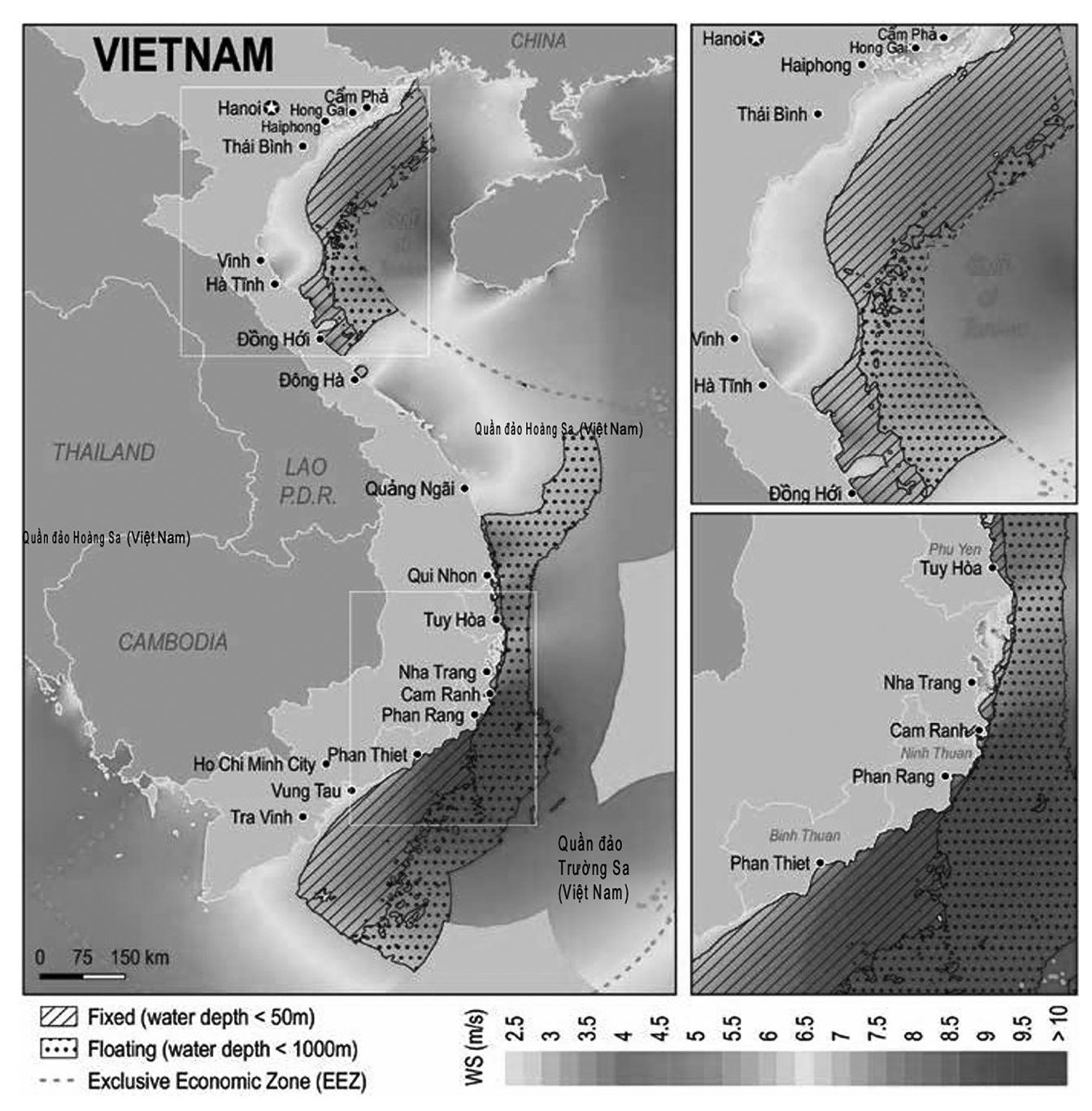

Figure 5. Vietnam's offshore wind power potential [4]

3. Opportunities and challenges in developing offshore wind power in Vietnam

3.1. Opportunities

Vietnam is presented with numerous opportunities and favorable conditions for developing offshore wind power, with significant natural potential and supportive policy directions. Firstly, Vietnam's strong commitment at the 26th Conference of the Parties (COP26) to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change to achieve net-zero emissions by 2050 demonstrates a high level of political will to transition to a green and clean energy economy. This aligns with the global trend of focusing on renewable energy sources, particularly wind and solar power. This policy creates an opportunity for the development of offshore wind power in Vietnam amidst rising energy demands.

Table1. List of Projects and Capacity by Province

|

No |

Province |

Number of Proposed Projects |

Capacity (MW) |

|

1 |

Quang Ninh |

2 |

6,000 |

|

2 |

Hai Phong |

5 |

16,200 |

|

3 |

Thai Binh |

2 |

3,700 |

|

4 |

Nam Dinh |

1 |

12,000 |

|

5 |

Thanh Hoa |

1 |

5,000 |

|

6 |

Ha Tinh |

2 |

1,050 |

|

7 |

Quang Binh |

5 |

4,109 |

|

8 |

Quang Tri |

4 |

3,600 |

|

9 |

Binh Dinh |

7 |

8,600 |

|

10 |

Phu Yen |

8 |

3,350 |

|

11 |

Ninh Thuan |

27 |

29,802 |

|

12 |

BinhThuan |

10 |

30,200 |

|

13 |

Ba Ria - Vung Tau |

7 |

6,160 |

|

14 |

Tra Vinh |

7 |

10,300 |

|

15 |

Soc Trang |

4 |

4,900 |

|

16 |

Vinh Long |

2 |

400 |

|

17 |

Ben Tre |

9 |

7,460 |

|

18 |

Bac Lieu |

10 |

5,255 |

|

19 |

Kien Giang |

1 |

236 |

|

20 |

Ca Mau |

6 |

8,500 |

|

Total |

120 |

166,822 |

|

Vietnam is naturally endowed with abundant offshore wind power potential. Figure 5 illustrates the distribution map of offshore wind speeds and potential areas for fixed-bottom and floating wind turbines [4]. Preliminary assessments suggest that the total technical potential could reach approximately 600 GW, several times the total capacity of the country’s existing power sources. Of this, about 261 GW are fixed-bottom offshore wind projects in waters less than 50 meters deep, and 338 GW are floating wind projects in deeper waters [4]. Many coastal areas have average wind speeds exceeding 10 m/s, which are highly suitable for large-scale wind farms. This significant natural advantage allows Vietnam to develop offshore wind power on a large and long-term scale.

The Communist Party and the State of Vietnam have shown particular interest and consistent direction in boosting the exploitation of marine economic potential in general and offshore wind power in particular through a series of recent key resolutions and strategies. Notably, Resolution No.36-NQ/TW dated October 22, 2018, from the Politburo on the Strategy for Sustainable Development of Vietnam's Marine Economy to 2030, with a vision to 2045, identifies "renewable energy and new marine economic sectors" as a breakthrough pillar. Following that, Resolution No.55-NQ/TW dated February 11, 2020, on the orientation of the National Energy Development Strategy of Vietnam to 2030, with a vision to 2045, emphasizes "establishing support policies and breakthrough mechanisms for offshore wind power development linked to the implementation of the Vietnam Marine Strategy." This provides an important basis for ministries, sectors, and localities to develop and implement specific action programs. The government has issued Resolution No.26/NQ-CP dated March 5, 2020, on the Master Plan and the 5-Year Plan for implementing Resolution 36-NQ/TW dated October 22, 2018, from the 8th Central Executive Committee meeting of the 12th Party Congress on the Strategy for Sustainable Development of Vietnam's Marine Economy to 2030, with a vision to 2045; and Resolution No. 140/NQ-CP dated October 2, 2020, to issue the Government's Action Program to implement Resolution No.55-NQ/TW dated February 11, 2020, from the Politburo on the orientation of the National Energy Development Strategy of Vietnam to 2030, with a vision to 2045, creating a consistent and unified legal framework from central to local levels.

A series of recent decisions by the Prime Minister have established goals, tasks, and solutions for ministries and sectors to implement these strategic directions.The Green Growth Strategy for the period 2021-2030 (Decision 1658/QĐ-TTg) identifies priority green economic sectors, including renewable energy. Decision 841/QĐ-TTg of 2023 positions sustainable energy development and improving access to reliable, sustainable energy as a pillar in Vietnam's roadmap for achieving the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). Particularly, the National Power Development Plan for the period 2021-2030, with a vision to 2050 (Power Development Plan VIII), approved by the Government in Decision No. 500/QĐ-TTg on May 15, 2023, specifically sets targets for increasing the share of offshore wind power, aiming for 6 GW by 2030 and 70-91 GW by 2050. The Government has approved the implementation plan for Power Development Plan VIII, which outlines the roadmap for key projects. These decisions demonstrate a strong political commitment by the Government to offshore wind power development in the coming period.

The World Bank's analysis shows a positive outlook on the feasibility and investment efficiency of offshore wind power. Since 2012, investment costs have significantly decreased, from $255/MWh to about $80/MWh. With this trend, the cost of offshore wind power could drop to about $58/MWh by 2030. This narrowing cost gap compared to traditional power sources indicates the increasing competitiveness and commercial potential of offshore wind power, which will be an important factor in attracting private and international investment. In the World Bank's high scenario, Vietnam's installed offshore wind capacity could reach 70 GW by 2050, making it the third-largest in Asia, after China and Japan.

Vietnam has been developing a certain legal framework related to maritime activities and wind power projects, facilitating deeper implementation of offshore wind projects in the near future. The 2012 Law of the Sea of Vietnam and the 2015 Law on Natural Resources and Environment of Sea and Islands have laid the foundation for economic exploration and exploitation activities in Vietnam's maritime areas. Government Decree No.51/2014/ND-CP of May 21, 2014, on the allocation of specific sea areas to organizations and individuals for marine resource exploitation, has been replaced by Decree No.11/2021/ND-CP of February 10, 2021. Decision No.37/2011/QD-TTg, as amended by Decision 39/2018/QD-TTg, has also introduced important support mechanisms for wind power development, such as tax incentives, land use, and electricity purchase prices. The Ministry of Industry and Trade's Circular No.02/2019/TT-BCT provides specific guidance on the procedures for developing wind power projects. Recently, the Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment has completed a draft decree supplementing regulations on the documentation, appraisal, and licensing of activities related to marine resource observation and assessment. These legal documents will create an initial legal framework for participants in Vietnam's offshore wind power market.

Overall, offshore wind power in Vietnam has very favorable conditions to take off in the coming period. With abundant natural potential, consistent policies and directions from the Party and State, and strong political commitments to combating climate change and reducing carbon emissions, there is a great opportunity for offshore wind power development. Furthermore, if cost trends continue to decline and the legal framework continues to improve, the attractiveness of Vietnam's offshore wind power market will only increase. However, to effectively capitalize on this potential, it is necessary to address existing challenges and barriers through comprehensive measures, including institutional improvements and resource mobilization.

Table 1 provides information on the number of projects and capacity (MW) of wind power plants in 20 provinces registered for development under Power Development Plan VIII. The number of registered offshore wind power projects ranges from 1 to 27 projects per province. Ninh Thuan has the largest number of projects with 27, followed by Binh Thuan and Bac Lieu with 10 projects each. Kien Giang and Nam Dinh have the fewest projects, with only 1 each.

There is also a significant disparity in capacity between provinces, ranging from 236 MW in Kien Giang to 30,200 MW in Binh Thuan. In addition to Binh Thuan, provinces registering large offshore wind power capacities include Ninh Thuan (29,802 MW), Tra Vinh (10,300 MW), Ba Ria - Vung Tau (6,160 MW), and Binh Dinh (8,600 MW).

In total, the country has 120 registered offshore wind power plant projects with a total capacity of 166,822 MW. Table 1 highlights the potential for developing renewable energy from offshore wind in many coastal provinces of Vietnam, particularly in the South Central and Southern regions.

3.2. Challenges

Despite the significant potential and opportunities, the development of offshore wind power in Vietnam faces numerous barriers and challenges from various aspects.

3.2.1. Legal framework

The legal and policy framework specifically for offshore wind power is still lacking and inconsistent. Vietnam does not yet have specific legal documents regulating this sector, with the topic only briefly mentioned in the 2023 Power Development Plan VIII. While the 2012 Law of the Sea of Vietnam provides general regulations on allocating sea areas to organizations and individuals for resource exploitation, there are no specific guidelines for allocating sea areas for developing renewable energy projects such as wind power.

Similarly, the 2015 Law on Natural Resources and Environment of Sea and Islands only addresses scientific research activities on the sea by foreign entities and does not cover the survey and construction of marine economic projects in general, nor offshore wind power projects with private investment in particular. The 2020 Environmental Protection Law lacks specific regulations and guidelines for environmental impact assessments for marine renewable energy projects. The absence of a consistent and detailed legal framework has created gaps and bottlenecks, causing confusion among stakeholders in the licensing, construction, appraisal, and implementation of projects.

Due to the high initial investment costs, offshore wind power requires more special incentive policies and support compared to onshore renewable energy projects. However, Vietnam has not yet established a specific electricity pricing mechanism, tax incentives, fee reductions, land use benefits for sea areas, or long-term financial support for offshore wind projects. Additionally, administrative barriers and investment and construction procedures remain complex and time-consuming due to overlapping regulations and the involvement of multiple ministries and agencies.

Planning and potential assessment are not yet truly consistent and effective. The power development planning has not been integrated with other marine sectors and field plans. Data on wind measurement, geological, and topographical assessments, as well as other technical factors necessary for planning, are still incomplete, unsystematic, and inaccurate. Therefore, coordination among State agencies in evaluating and reaching consensus on suitable marine areas needs further improvement.

Technical infrastructure for grid connection, as well as supply chain and logistics services for offshore wind power, remain limited. The current power transmission grid has not been planned to meet the demand for integrating large and distant offshore wind sources in the future, necessitating investment in upgrades. Port infrastructure, roadways, and storage facilities in potential coastal areas do not meet the stringent technical requirements for the installation, operation, and maintenance of large-scale offshore wind farms. Experience with large-scale offshore wind projects is still new for maritime service providers, surveyors, and marine construction companies. These factors pose difficulties and risks for implementing large-scale wind power projects and significantly increase investment costs.

Inter-agency coordination and shared responsibility among ministries and sectors in policy implementation also present challenges for offshore wind power development. The Ministry of Industry and Trade believes that investors must bear all risks during surveys due to the lack of specific planning, along with unclear issues such as survey licensing authority, investment policy approval, and the absence of regulations on conditions for foreign investors. The Ministry of National Defense requires adjustments to project scale if there is overlap with defense areas and emphasizes maritime safety. The Ministry of Public Security notes that current regulations do not allow foreign organizations to conduct surveys and lack clear provisions on the procedures for approving and managing marine survey activities. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs stresses the need to comply with regulations on port security and foreign activities in Vietnamese waters. The Ministry of Transport disagrees with granting survey permits in areas overlapping with national maritime routes. The Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development also points out that surveys should not affect conservation areas and aquaculture zones. The differing viewpoints among ministries highlight the need to further enhance the coordinating role and problem-solving capacity of State management agencies regarding offshore wind power.

3.2.2. Technical obstacles

The development of offshore wind power in Vietnam faces several technical barriers that need to be addressed promptly. Vietnam currently lacks specific standards regarding the area of sea permitted for use in surveying and assessing project potential per unit of capacity (ha/MW). This requirement can vary significantly depending on the characteristics of each marine area, such as wind speed, depth, geological foundation quality, and the type of turbine used. Determining the optimal capacity for a project is also an unresolved issue due to the lack of appropriate guidelines and criteria. A project that is too small may not attract major investors, while one that is too large can create challenges for the transmission system.

Vietnam has yet to establish a long-term plan for the total offshore wind power capacity to be surveyed in each planning phase to ensure feasibility and alignment with established targets. The criteria for selecting project developers are also unclear, making it difficult to filter out entities with the necessary capabilities, experience, and commitment. Planning for prospective marine areas for wind power development requires more systematic investment to provide direction for investors and management agencies.

These technical barriers indicate the necessity of thoroughly researching and issuing specialized technical regulations and standards for offshore wind power.

3.2.3. Other obstacles

State management agencies still lack a unified understanding of whether to permit foreign organizations and individuals to conduct wind, geological, and topographical surveys in Vietnamese waters. This lack of clarity creates difficulties for international investors looking to enter the market, while also limiting the ability to learn from the experience and technology of more advanced countries.

Detailed regulations regarding the documentation, procedures, and timelines for approving activities related to marine resource investigation, survey, and assessment have yet to be clearly outlined, leading to prolonged licensing processes and project delays.

Current regulations lack clear guidelines on how to handle situations where multiple entities propose overlapping surveys in the same marine area. It is unclear whether the parties are allowed to conduct surveys together or if a single entity must be selected through a bidding process.

The maximum time for authorities to review and approve applications for wind, geological, topographical surveys, and environmental impact assessments is not clearly stipulated, leading to delays in approvals, increased costs, and risks for investors.

Additionally, the issuance of survey permits should specify a clear validity period to provide stability and confidence for investors to proceed with their projects. However, this is still lacking in the relevant legal documents.

Vietnam does not yet have a mandatory requirement for project developers to submit survey results to the approving agency, nor are there guidelines on the content and timing of such reports. Consequently, state agencies face difficulties in monitoring information, overseeing progress, and ensuring the quality of surveys.

4. Some solutions for offshore wind development in Viet Nam

Based on the analysis of opportunities and challenges in developing offshore wind power in Vietnam, the following key solutions are proposed:

Firstly, it is necessary to complete a comprehensive and specialized legal framework for offshore wind power development. In the short term, priority should be given to amending and supplementing overlapping and inadequate provisions in the Electricity Law, Renewable Energy Law, Law on Marine Resources and Environment, and related guiding documents. Specifically, a separate Decree on licensing for potential surveys, project development, and exploitation of offshore wind power should be issued promptly, clearly outlining the procedures, timelines, and responsibilities of all relevant parties. In the long term, consideration should be given to developing a National Assembly Resolution for piloting offshore wind power development and a specialized Law on offshore wind power to create a robust legal framework.

Secondly, there is a need to research and issue long-term incentive mechanisms and policies to encourage domestic and international private investment. These policies should include competitive bidding mechanisms and separate preferential electricity purchase prices, support in taxes, fees, seabed lease costs, credit guarantee mechanisms, and dedicated development funds for offshore wind power. Additionally, policies are needed to encourage technology transfer, local production of equipment, and the development of domestic supply chains for the offshore wind industry.

Thirdly, a centralized state management agency directly under the Government should be established to uniformly direct the formulation of strategies and master plans for national-level offshore wind power. This agency would also be responsible for licensing and supporting projects through a single-window mechanism, coordinating with relevant ministries, sectors, and localities to resolve obstacles and shorten project implementation timelines.

Fourthly, research, training, and technology transfer centers should be established, and cooperation with countries with advanced offshore wind industries should be strengthened. Comprehensive training programs on offshore wind power engineering and project management should be developed to proactively build a high-quality workforce for this sector.

Fifthly, offshore wind power development planning needs to be prioritized to provide a foundational orientation for investors. The National Marine Spatial Planning should be approved and implemented urgently, clearly identifying priority marine areas for renewable energy development. This planning must be integrated and harmonized with other sectoral plans, such as marine conservation, transportation, mining, tourism, and national security and defense. Databases on wind, geology, and the marine environment should also be digitized and made widely accessible to relevant stakeholders.

Sixthly, persistence and consistency are required in attracting and effectively utilizing international financial resources for offshore wind power development. Vietnam should proactively engage in and leverage programs and support funds from international organizations and developed countries for renewable energy transition. Actively seeking foreign investment, particularly from countries with experience and strong investment potential in offshore wind projects, and mobilizing green funds, green bonds, and clean technology support capital will also play a crucial role in achieving the set goals.

Seventhly, Vietnam should actively participate more in international cooperation networks for offshore wind power development, sharing information, learning management experiences, policy creation, and practical project implementation from leading countries such as the United Kingdom, Denmark, Germany, and China.

5. Conclusion

The article has synthesised and analysed the opportunities and challenges in policies and laws serving the development of renewable energy in Vietnam today to achieve the goals in the National Power Development Plan VIII. The article also pointed out the existing challenges in developing renewable energy and proposed regulations that need to be removed.

Dư Văn Toán1, Ngo Thuy Hao2, Phạm Quý Ngọc3 Du Thi Viet Nga

1Institute of Environment, Sea and Island Science, MONRE

2Xiamem University, China

3Petroleum Institute PVN

4Wuhan University of Geoscience, China

(Source: The article was published on the Environment Magazine by English No. IV/2024)

References