11/12/2025

The sixteenth edition of the United Nations Environment Programme's (UNEP) Emissions Gap Report (EGR) 2025: Off Target, reveals a persistent and perilous chasm between climate ambition and the emissions pathways required to meet the Paris Agreement goals. This paper critically analyzes the report's key findings, specifically focusing on the minimal trajectory shift resulting from updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs), the alarming forecast for a 1.5°C overshoot, and the necessary scale of decarbonization required by 2035. While the projections under NDCs have slightly improved to 2.3°C - 2.5°C (down from 2.6°C - 2.8°C), this marginal gain is insufficient to avoid a major escalation of climate risks. The analysis emphasizes the necessity of immediate, system-wide transformations across energy, finance, and land-use sectors, arguing that the political will to accelerate near-term cuts remains the most formidable barrier to limiting the extent and duration of the predicted temperature overshoot.

1. The enduring gap

The report finds that this overshoot must be limited through faster and bigger reductions in greenhouse gas emissions to minimize climate risks and damages and keep returning to 1.5°C by 2100 within the realms of possibility - although doing so will be extremely challenging. Every fraction of a degree avoided means lower losses for people and ecosystems, lower costs, and less reliance on uncertain carbon dioxide removal techniques to return to 1.5°C by 2100. Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement ten years ago, temperature predictions have fallen from 3-3.5°C. The required low-carbon technologies to deliver big emission cuts are available. Wind and solar energy development is booming, lowering deployment costs. This means the international community can accelerate climate action, should they choose to do so. However, delivering faster cuts requires would require navigating a challenging geopolitical environment, delivering a massive increase in support to developing countries, and redesigning the international financial architecture.

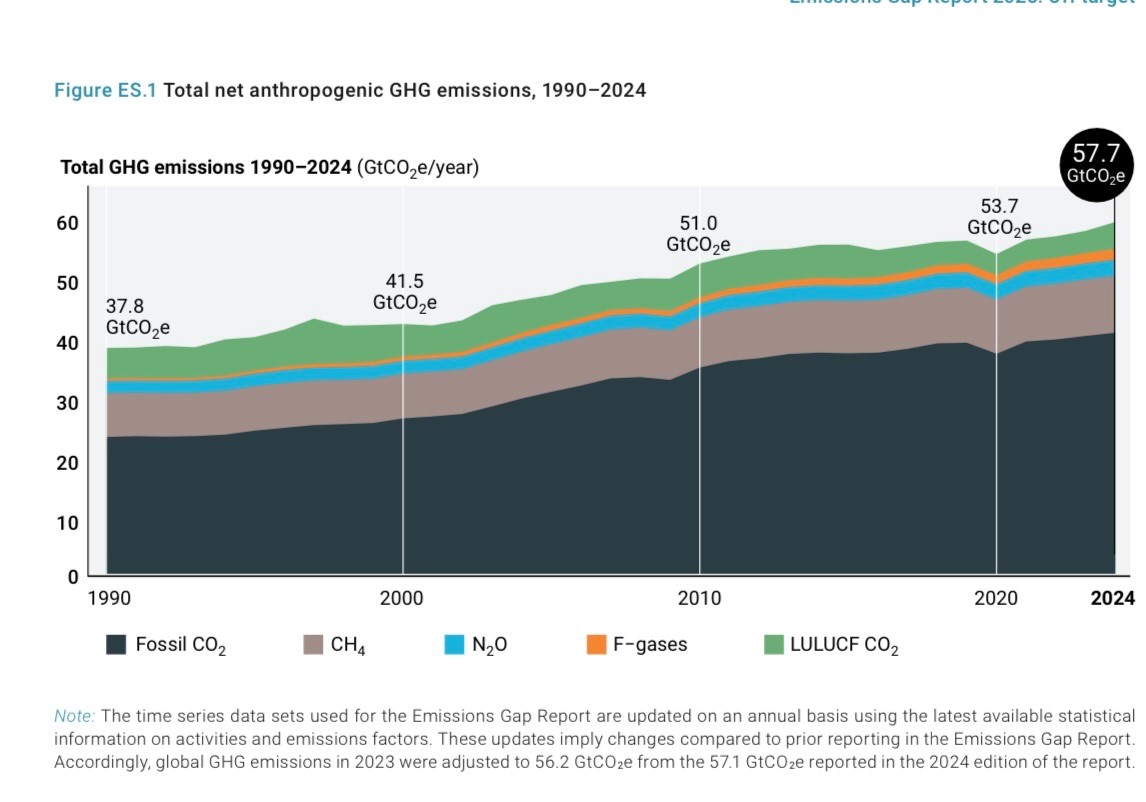

The total net anthropogenic GHG emissions, 1990 – 2024

(Source: www.unep.org)

The annual UNEP Emissions Gap Report is the authoritative scientific assessment tracking global progress toward the temperature targets of the Paris Agreement. The EGR 2025 is particularly significant as it follows the third major cycle for submitting NDCs, setting the baseline for the global stocktake cycle. Despite mounting climate impacts and increasing technological readiness, the report's overarching message is one of insufficient ambition and delayed action. This article dissects the core findings of EGR 2025, contrasting current policy trajectories with required pathways and assessing the political and economic implications of the projected temperature overshoot.

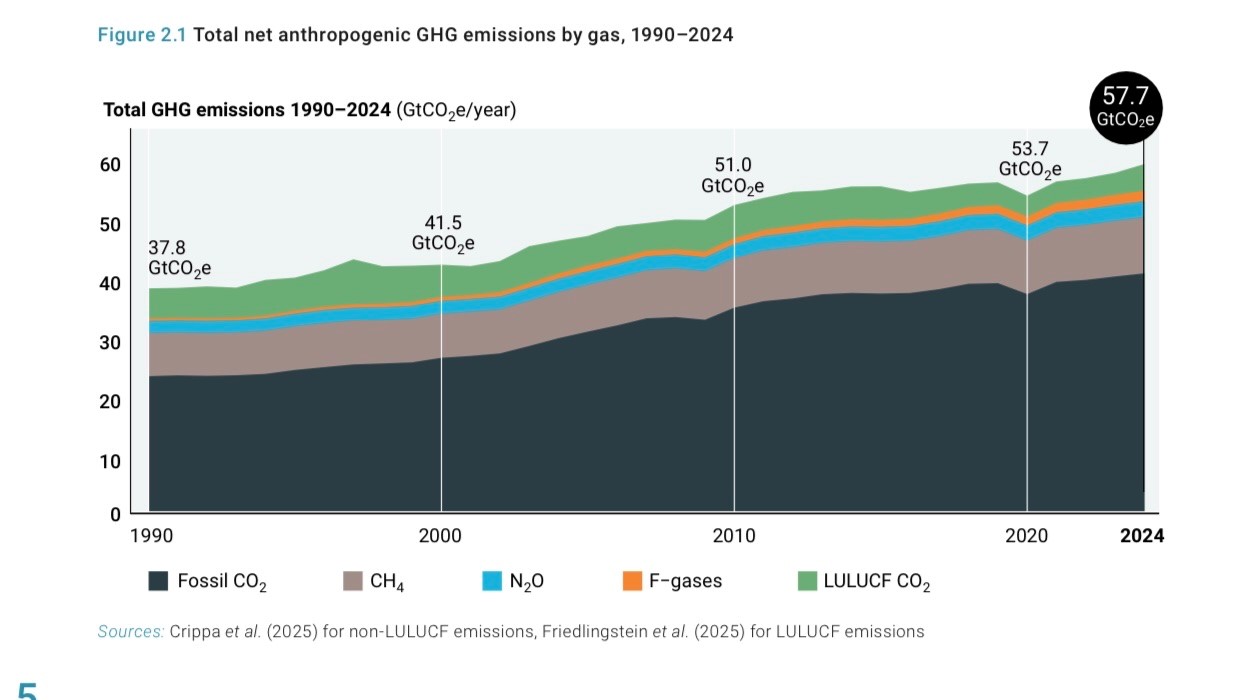

The total net anthropogenic GHG emissions by gas, 1990 – 2024

(Source: www.unep.org)

2. Global emissions trends

The Emissions Gap Report focuses on total net GHG emissions across all major groups of anthropogenic sources and sinks reported under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC). This includes carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from fossil fuels and industry (fossil CO2); CO2 emissions and removals from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF CO2); methane emissions (CH4); nitrous oxide emissions (N2O); and fluorinated gas (F-gas) emissions covered under UNFCCC reporting. It excludes ozone-depleting substances regulated under the Montreal Protocol, as well as the cement carbonation sink, neither of which are currently covered in UNFCCC reporting. It also excludes fire emissions not covered by inventory or bookkeeping model reporting. Including these various sources would increase global emissions by approximately 1.8 GtCO2e per year. Global totals include all countries and international aviation and shipping emissions. Where national estimates are reported, emissions are attributed to the country in which they are produced (territorial accounting). The reporting of net LULUCF CO2 emissions is consistent with previous Emissions Gap Reports.

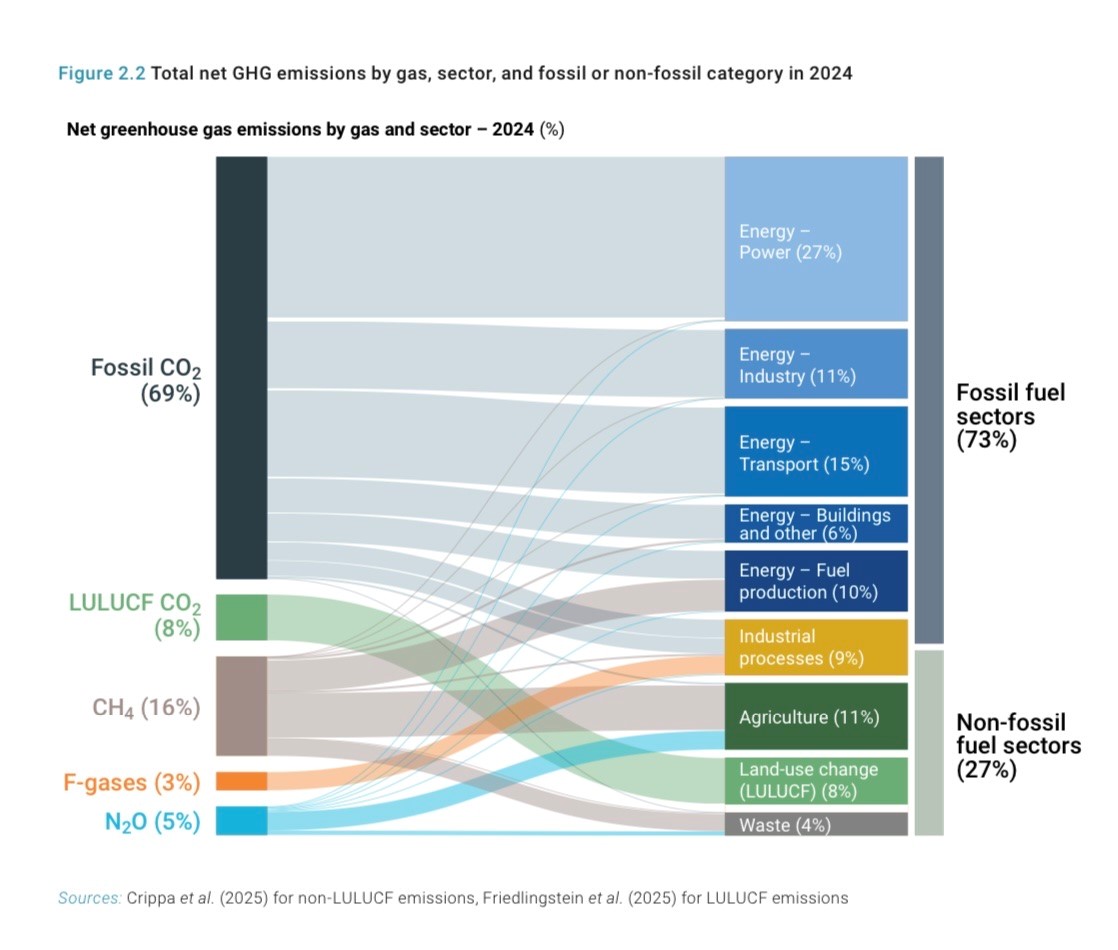

The total net GHG emissions by gas, sector and fossil or non-fossil category in 2024. (Source: www.unep.org)

Global greenhouse gas emissions continued to increase in 2024: Ten years on from the adoption of the Paris Agreement, global GHG emissions continue to increase. In 2024, they reached a record of 57.7 GtCO2e, representing a 2.3 per cent (1.4 GtCO2e) increase from the previous year. This rate is high compared with the 2023 growth rate (1.6 per cent). It is more than four times higher than the annual average growth rate in the 2010s (0.6 per cent per year) and comparable to that of the 2000s (on average 2.2 per cent per year). At the same time, atmospheric CO2 concentrations rose to 423.9 parts per million in 2024, while CH4 and N2O concentrations also continued to increase. Since atmospheric GHG concentrations drive global warming, these are ultimately the metrics that matter for meeting the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement.

The impacts of deforestation and wildfires on local populations including loss of lives, public health, impacts on property and infrastructure, and other economic impacts underscores the need to look at these events beyond emissions. Wildfire smoke can travel long distances causing air pollution and harming regional health, while black carbon speeds up glacier melt. Wildfires and deforestation are accelerating habitat fragmentation, pushing thousands of species closer to extinction. The disruption of ecological networks and loss of keystone species also undermines ecosystem resilience, with cascading effects on food security, water regulation and disease control.

Emissions continued to increase across major sectors: Focusing on the energy sector, overall energy demand increased by 2.2 per cent in 2024, which was higher than the average rate of demand increase observed between 2013 and 2023. Combined with a recovery of hydropower generation, much of the increase in energy demand in 2024 was met by non-fossil sources. The year 2024 was another record year for renewable electricity generation. The increased adoption of renewable energy, combined with the declining share of thermal power and with energy efficiency improvements, have resulted in a steady decline in the global CO2 intensity of electricity since 2007. Other emerging sources of demand included electric vehicles, heat pumps and data centres, which collectively contributed to an additional 200 TWh or 0.7 per cent of global demand growth.

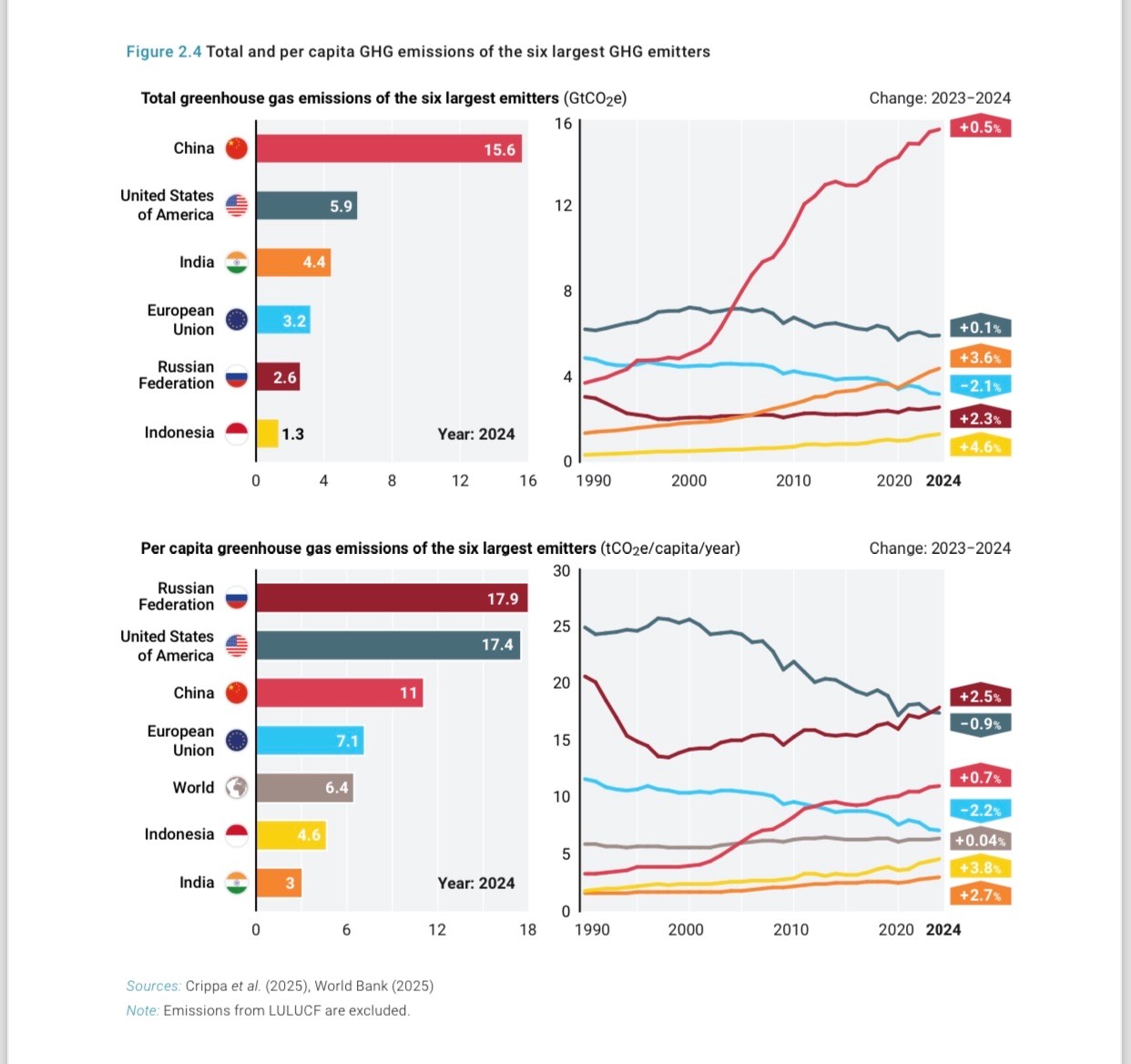

Emissions increased for all but one of the largest GHG emitters: Preliminary estimates for 2024 (which exclude national-level LULUCF CO2, for which data is only available up to 2023) show an increase in GHG emissions compared with 2023 in all of these except the European Union. Emissions inequality continues to exist within countries, with the richest individuals driving emissions with their consumption and investments, and few policies addressing this globally.

3. Key findings of the EGR 2025: Minimal movement, maximal risk

3.1. The illusion of progress

The EGR 2025 indicates that full implementation of available new NDCs would limit global warming this century to 2.3°C - 2.5°C above pre-industrial levels. While statistically lower than last year's forecast, the report cautions that this improvement is partially attributable to methodological updates and is significantly offset by factors such as the withdrawal of certain major economies from the Paris Agreement.

Current policies gap: The report’s "Current Policies" scenario remains deeply concerning, pointing to a warming of up to 2.8°C, highlighting a severe implementation gap where national actions fail to even meet existing, often inadequate, commitments.

The report finds that only 60 Parties to the Paris Agreement, covering 63 per cent of greenhouse gas emissions, had submitted or announced new NDCs containing mitigation targets for 2035 by 30th September 2025. In addition to the lack of progress in pledges, a huge implementation gap remains, with countries not on track to meet their 2030 NDCs, let alone new 2035 targets.

Aligning with the Paris Agreement requires rapid and unprecedented cuts to greenhouse gas emissions above the pledges - a task made harder by emissions growing 2.3 per cent year-on-year to 57.7 gigatons of CO2 equivalent in 2024. Emissions in 2030 would have to fall 25 per cent from 2019 levels for 2°C pathways, and 40 per cent for 1.5°C pathways – with only five years left to achieve this goal.

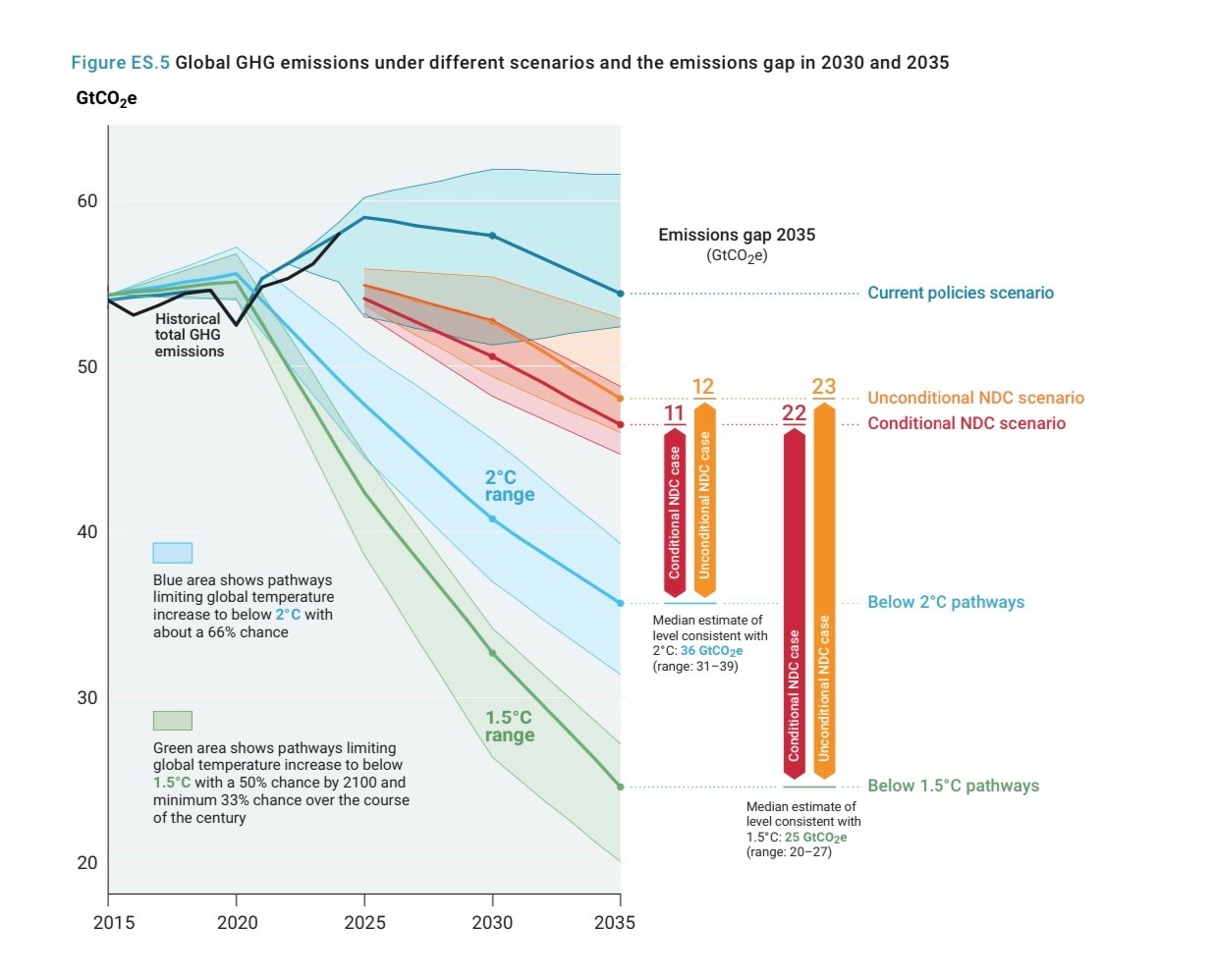

Full implementation of all NDCs would reduce expected global emissions in 2035 by about 15 per cent compared with 2019 levels although the US withdrawal will change these figures. These reductions are far below the 35 per cent and 55 per cent needed in 2035 to align with 2°C and 1.5°C pathways, respectively.

The 1.5°C threshold: The size of the cuts required, and the short time left to deliver them, means that the multi-decadal average of global temperature will now exceed 1.5°C, very likely within the next decade. Stringent near-term cuts to emissions could delay the onset of overshoot, but not avoid it entirely. The big task ahead is to strive to make this overshoot temporary and minimal, through rapid emissions cuts that keep returning to 1.5°C by 2100 in the realms of possibility.

Every fraction of a degree avoided reduces an escalation of the damages, losses and health impacts that are harming all nations while hitting the poorest and most vulnerable the hardest and reduces the risks of climate tipping points and other irreversible impacts. Minimizing overshoot would also reduce reliance on uncertain, risky and costly carbon dioxide removal methods which would need to permanently remove and store about five years of current global annual CO2 emissions to reverse each 0.1°C of overshoot

The report looks at a "rapid mitigation action from 2025” scenario, which is designed to limit overshoot to about 0.3°C, with a 66 per cent chance, and return to 1.5°C by 2100. Under this scenario, 2030 emissions would have to fall by 26 per cent and 2035 emissions by 46 per cent compared with 2019 levels.

3.2. The inevitable overshoot and the 2035 imperative

A crucial finding is the increased certainty that the multi-decadal average global temperature will exceed the 1.5°C threshold, highly likely within the next decade. This reinforces the shift in climate discourse from avoiding 1.5°C to limiting the duration and magnitude of the overshoot.

Required emissions cuts: To align with the 1.5°C pathway, global annual emissions must fall by approximately 55% by 2035 (compared to 2019 levels). For the less ambitious 2°C pathway, a 35% reduction is required by the same date. The vast distance between the current 12-15% cut and the required 55% defines the scale of the Emissions Gap.

Global GHG emissions under different scenarios and the emissions gap in 2030 and 2035 (Source: www.unep.org)

3.3. Sectoral and regional dynamics

The report provides granular data on where the emissions growth originates, noting that fossil CO2 emissions continue to rise, and highlights an alarming spike in emissions from Land Use, Land-Use Change, and Forestry (LULUCF).

Since the adoption of the Paris Agreement ten years ago, temperature predictions have fallen from 3-3.5°C. The required low-carbon technologies to deliver big emission cuts are available. Wind and solar energy development is booming, lowering deployment costs. This means the international community can accelerate climate action, should they choose to do so. However, delivering faster cuts would require navigating a challenging geopolitical environment, a massive increase in support to developing countries, and redesigning the international financial architecture.

G20 action and leadership will be pivotal as G20 members - excluding the African Union – account for 77 per cent of global emissions. Seven G20 members have submitted new NDCs with targets for 2035, while three members have announced such targets. However, these pledges are not ambitious enough, G20 members are collectively not on track to achieve even their 2030 NDC targets, and G20 emissions rose by 0.7 per cent in 2024 - all pointing to the need for a massive ramp up in action by the biggest emitters.

Emerging progress: The report acknowledges that in certain large economies, the rapid growth of renewable energy (solar and wind) is beginning to outpace power demand growth, offering a glimpse of potential peak emissions.

The fundamental ingredient for progress towards the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement remains unchanged: immediate and stringent emission reductions. Unprecedented mitigation action will be essential to minimize the level and duration of overshoot and reliance on uncertain removal technologies. Considerable knowledge exists regarding the options, benefits and opportunities of accelerated mitigation action. In many cases, mitigation aligns with economic growth, job creation, energy security.

Required technologies are available, and wind and solar energy development, continue to exceed expectations, lowering deployment costs and driving market expansion (UNEP 2024; United Nations 2025). Yet deployment remains insufficient. Accelerated emission reductions require overcoming policy, governance, institutional and technical barriers; unparalleled increase in support to developing countries; and redesigning the international financial architecture. The new NDCs and current geopolitical situation do not provide promising signs that this will happen, but that is what countries, and the multilateral processes, must resolve to affirm collective commitment and confidence in achieving the temperature goal of the Paris Agreement.

4. Policy implications and the way forward

The Paris Agreement builds on a five-year ambition-raising cycle, whereby parties are requested to ratchet up the ambition of their mitigation efforts over time to align with the temperature goal and other goals of the agreement. The new nationally determined contributions (NDCs) that countries are required to submit this year are therefore a critical test of the ambition-raising mechanism. The extent to which parties respond with enhanced ambition and implementation grounded in the principle of equity, including gender equity, and common but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities, in the light of different national circumstances influences the credibility of the Paris Agreement and the world’s ability to close the emissions gap.

NDCs have become slightly more robust over time but this evolution has been slow, and the new NDCs have done little to accelerate progress: This section assesses the new NDCs against language in the Paris Agreement and the first global stocktake. First, it examines the stipulation in the Paris Agreement that developed countries’ NDCs should contain economy-wide, absolute emission reduction targets, while developing countries are encouraged to move over time towards economy-wide targets. Second, it considers the call in the global stocktake for parties to submit “ambitious, economy wide emission reduction targets, covering all GHGs, sectors and categories” (UNFCCC 2023). The number of parties with GHG targets has risen only slightly with the new NDCs. The new NDCs do reflect an incremental shift in GHG targets to more robust 15 formulations, but have not noticeably broadened the scope of sectors and gases covered by the targets. Parties are also increasingly considering gender in their NDCs to promote inclusive and effective climate action Parties have not materially improved the sector and gas coverage of targets in their most recent NDCs. Moreover, while several decisions since the twenty-sixth session of the Conference of the Parties to the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (COP 26) have requested countries to revisit and strengthen their 2030 targets.

Alignment with sectoral elements of the global stocktake outcome is still lacking: The global stocktake set targets to triple renewable energy capacity and double the annual rate of energy efficiency improvement by 2030. The latest available assessments, based on active NDCs in 2024, indicate that renewable energy capacity would increase by 2.0-2.2 times (International Renewable Energy Agency [IRENA] 2024; International Energy Agency [IEA] 2025), falling well short of the tripling target. These commitments appear conservative, however, in light of prevailing policies and market dynamics, which look to increase capacity by 2.7 times (IEA 2025), much closer to (though still short of) the tripling goal. While it is not yet clear to what extent the new NDCs will increase progress on this point, it is encouraging that 70 per cent of them now contain a renewable capacity target.

Total and per capital GHG emissions of the six largest GHG emitters (Source: www.unep.org)

Regarding energy efficiency, active NDCs in 2024 would increase the global efficiency improvement rate by an average of 2.8 per cent per year through to 2030 (IEA 2024), falling short of the global stocktake goal of doubling the improvement rate.

In addition to these specific targets, the global stocktake outlines a range of global efforts to reduce reliance on fossil fuels. While these are not quantified, the International Energy Agency (IEA)’s net-zero scenario provides benchmarks against which NDCs might be measured. With regard to the new NDCs, more than half (62 per cent) set a target to reduce fossil fuel use in the electricity mix, while 29 per cent set a coal-phasedown target. To date, however, no NDCs set targets to reduce oil and gas production or trim inefficient fossil fuel subsidies.

There is scope for increased clarity on conditionality and finance: The Paris Agreement requires that mitigation efforts in developing country parties be supported with finance, technology and capacity-building, and many parties have proposed NDCs that are fully or partially conditional on receiving such support. The Emissions Gap Report 2024 proposed that new NDCs should be “explicit about conditional and unconditional elements, with emerging market and developing economies providing details on the means of implementation they need, including institutional and policy change, as well as international support and finance required to achieve ambitious NDC targets for 2035.”

The findings highlight the need for stronger investment and implementation planning in future NDCs. More international cooperation and support in preparing NDCs would help, particularly for emerging market and developing economies. Development finance institutions and private advisory groups can provide technical expertise and data infrastructure, and offer capacity-building programmes aimed at improving national investment planning capabilities. In sum, better investment ‘signaling’ in NDCs linked to sound policies, enabling frameworks, and price incentives will help attract climate finance that is aligned with development priorities. However, it should be noted that investment signals in NDCs in isolation are not enough to attract climate finance. Strong policies, enabling frameworks and price incentives remain key to enabling investment in NDCs and climate objectives.

G20 emissions pathways towards 2035: It also provides a preliminary assessment of the new NDCs and the extent to which they represent strengthened mitigation ambition, per capita emissions and peaking of emissions and net-zero emission pledges. Each G20 member historical emissions between 2000 and 2023 based on national GHG inventories; emission trajectories based on current policies; and target emission levels from 2030 and 2035 NDCs, as well as net zero targets.

Ten G20 members have submitted or announced new NDCs with mitigation targets for 2035. Current policies scenarios project GHG emissions based on policies already adopted and/or implemented. For 2030, the G20 aggregate emissions under current policies are projected to be 35 GtCO2e (sum of central estimates). While the results are largely similar to last year’s at the aggregate level.

For 2035, the G20 aggregate emissions under current policies are projected to drop to 33 GtCO2e, i.e. 2 GtCO2e lower than 2030’s figure (sum of central estimates). China is the largest contributor to this projected reduction (1 GtCO2e), followed by the European Union (0.6 GtCO2e) and the United States of America (0.2 GtCO2e). Other G20 members are on clear downward emission trends and several more might peak or plateau between 2030 and 2035 under current policies, while others are projected to continue increasing their emissions up to 2035.

A comparison of 2035 emissions under the new NDCs with those expected under current policies indicates whether the new NDCs represent increased mitigation ambition beyond what would result from policies already in place. This metric is key to assessing the ambition raising mechanism of the Paris Agreement.

Fully achieving 2035 pledges would reduce the per capita emissions levels of several high-income G20 members (e.g. the European Union, Japan and the United Kingdom) to levels similar to those of lower-middle-income members. Several high-income G20 members, however, are still on course to emit more than 10 tCO2e per capita in 2035, this is a higher level than that of almost all middle-income G20 members today.

The declining emissions trend observed for high-income G20 members is less apparent for middle-income G20 members. It is a positive sign, however, that many of these countries are projected not to increase their per capita emissions much beyond current levels despite their need for further economic development.

The outcome of the first global stocktake encourages parties to align their NDCs with 1.5°C, “as informed by the latest science, in the light of different national circumstances” (UNFCCC 2023). It also notes the importance of aligning NDCs with long-term, low emissions development strategies, which in turn are to be “towards just transitions to net-zero emissions.” The global stocktake recognizes that in scenarios limiting warming to 1.5°C (>50 per cent), global emissions reach their peak between 2020 and 2025, noting that “this does not imply peaking in all countries within this time frame, and that time frames for peaking may be shaped by sustainable development, poverty eradication needs and equity and be in line with different national circumstances” (UNFCCC 2023).

A country’s emissions are considered to have peaked if an established minimum time has passed since its year of maximum emissions (5 years and 10 years are the two time periods established, and calculations are done including and excluding LULUCF), and if its current policy trajectory indicates that future emissions will continue to decline in the years to 2035.

The EGR 2025 offers a sobering, yet actionable, framework for global climate governance. The "Gap" is not merely technical, but political and financial.

The report implicitly critiques the current state of climate finance. The disparity in technology readiness (e.g., cheap renewables) versus actual deployment in developing nations due to financial constraints and geopolitical fragmentation is a key barrier to closing the implementation gap. Reform of the global financial architecture and a massive increase in concessional and public climate finance are non-negotiable prerequisites.

Since a temporary 1.5°C overshoot is now likely, policymakers must focus on two critical areas: Minimizing Overshoot and Enhancing Adaptation. Deploying carbon removal technologies and nature-based solutions to create a pathway back below 1.5°C by 2100. Prioritizing adaptation finance and capacity building, particularly in vulnerable regions, to minimize loss and damage resulting from the period of overshoot.

5. Conclusion

The UNEP Emissions Gap Report 2025 serves as a decisive wake-up call, titled appropriately Off Target. The marginal improvement in long-term warming projections is overshadowed by the imminent breach of the 1.5°C limit, underscoring the collective failure of nations to align political action with scientific necessity. To bridge the 55% emissions gap required by 2035, the international community must move beyond incremental NDCs and initiate unprecedented, whole-of-society transformations. The window for limiting climate catastrophe is not merely closing; it is all but shut, making decisive action this decade the singular determinant of a habitable future.

Nguyễn Xuân Thắng

(Source: The article was published on the Environment Magazine by English No. IV/2025)

REFERENCES

1. https://www.unep.org/resources/emissions-gap-report-2025