11/12/2025

ABSTRACT

The research and development of a biofilter for whiteleg shrimp farming, intended for high-density cultivation, has been conducted in laboratory settings and practical applications. The results in the laboratory illustrate the high potential for application in practice. To guarantee the procedure's feasibility, it was deemed necessary to implement an experimental application of the process in a pond with an area of 500 m2. The parameters for the practical model have been determined for the mass balance of total ammonia, solids, dissolved oxygen, biofilter size, and flow time in the water circulation system. Experimental results indicate a high treatment efficiency, with H2S removal reaching approximately 77% and an increase in dissolved oxygen concentration ranging from 42% to 48%.

Key words: Super-intensive whiteleg; RAS, Biofilter, Litopenaeus vannamei.

1. INTRODUCTION

In recent years, aquaculture, especially shrimp farming, has grown significantly to satisfy the increasing need for seafood. Nonetheless, intensive shrimp farming methods frequently lead to numerous environmental problems, such as excessive water consumption and the release of nutrient-filled wastewater. Moreover, further boosting production under the current system will be difficult due to space constraints and the negative environmental effects of semi-intensive systems (Boyd et al., 2022). These issues have urgently demanded sustainable and environmentally friendly aquaculture systems. As a result, the adoption of super-intensive farming practices for whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) that conserve water and safeguard the environment has garnered considerable interest. This research paper intends to offer a detailed model of the water circulation system for super-intensive whiteleg shrimp ponds and highlight the significance of conducting more studies in this field. The suggested model presents a sustainable alternative to conventional shrimp farming techniques by incorporating biological technology and innovative practices. This approach reduces water usage and lessens the negative environmental effects linked to intensive aquaculture. The efficient use of water resources in aquaculture has emerged as a key priority. Farming super-intensive whiteleg shrimp involves high stocking densities that necessitate a substantial water supply to sustain optimal water quality and avoid disease outbreaks. As a result, conventional shrimp farming practices require considerable water usage, which results in economic inefficiencies and disruptions to the ecosystem. Addressing the need to increase production, improve nutrition, and guarantee food security while also reducing space requirements and environmental effects demands the creation of more sophisticated, well-regulated, and sustainable farming techniques (Nguyen et al., 2019). To tackle these issues, various methods have been suggested, including water recirculation systems, biofloc technology, and the use of advantageous microbial communities (Emerenciano et al., 2022; Krummenauer et al., 2011). Current super-intensive shrimp farming practices are more efficient, using less water per kilogram of shrimp, recycling water, attaining a lower feed conversion ratio, and making effective use of land and water resources (Villarreal & Juarez, 2022). The Mekong Delta is the main area for shrimp farming in Vietnam, accounting for nearly 89% of the nation's overall shrimp output. This region includes the five leading provinces in shrimp production: Ca Mau, Bac Lieu, Soc Trang, Ben Tre (old), and Kien Giang (Thi & Lan, 2013). Specifically, Vinh Long province is encountering difficulties due to deteriorating farming conditions, which are a result of ineffective disease management strategies, the release of wastewater from ponds, and the buildup of sediment at the bottom (Lang Ton et al., 2023). By integrating these strategies, the water circulation system model for super-intensive whiteleg shrimp ponds provides a comprehensive solution that enhances water efficiency and supports improved environmental sustainability. This model seeks to transform practices in the aquaculture industry by decreasing water exchange needs, lowering effluent discharge, and improving biofiltration efficiency. To sum up, the pressing demand for sustainable shrimp farming methods that preserve water and safeguard the environment calls for the creation of innovative and effective systems. The suggested model for the water circulation system in super-intensive whiteleg shrimp ponds offers a hopeful approach to tackle these issues. This research paper will examine the application of this model, assess its effectiveness, and emphasize its potential to transform the future of shrimp aquaculture.

2. METHODS

2.1. Subjects

The particular needs for wastewater treatment technology in Ben Tre province, combined with the nature of wastewater from super-intensive white-legged shrimp farming ponds, indicate that Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) technology is an ideal option, as it can recycle as much as 70% of the wastewater. The RAS is an aquaculture system that recirculates water by removing waste. Implementing RAS technology offers several advantages, including reduced water consumption, improved water quality, and increased productivity in farming whiteleg shrimp (Nugraha et al., 2023).

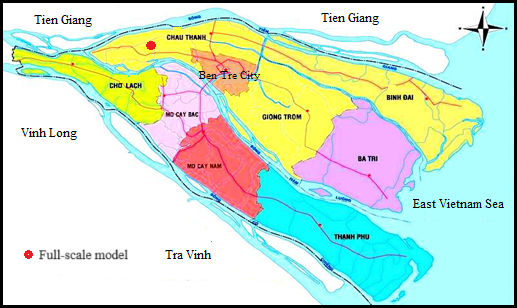

Figure 1: The study area

This technology utilizes both mechanical and biological filters to eliminate suspended particles and address pollutants like NO3, NH4+, BOD5, and H2S, ensuring compliance with the water quality standards outlined in QCVN 02-19:2014/BNNPTNT (MARD, 2014). The experimental modeling method includes laboratory and real-world models, with the laboratory models aiding in cost reduction and supplying crucial technical specifications for developing an effective system. The laboratory model also helps assess risks while the system is in operation, enabling the creation of efficient treatment strategies for practical use concerning both cost and effectiveness. The full-scale model of this study is located in Ben Tre province (old), as shown in Figure 1.

2.2. Methods

A detailed description of the research methods should be provided, including both a laboratory model operating at 1 m³/day and a full-scale model operating at 500 m³/day. The design parameters of the mechanical filter tank and biofilter tank are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2.

Table 1: Summary of mechanical filter tank design parameters

|

Parameters |

Symbol |

Unit |

Value |

|

|

Tank size |

Length |

L |

m |

0.95 |

|

Width |

W |

m |

0.45 |

|

|

Height |

H |

m |

0.45 |

|

|

Washing the filter manually |

||||

|

Filtration speed |

v |

m/h |

0.3 |

|

|

Wastewater inlet diameter |

D |

mm |

21 |

|

|

Wastewater outlet diameter |

D |

mm |

27 |

|

Table 2: Biofilter tank design parameters

|

Parameters |

Symbol |

Unit |

Value |

|

|

Tank size |

Length |

L |

m |

2 |

|

Width |

W |

m |

0.62 |

|

|

Height |

H |

m |

0.48 |

|

|

Main air duct diameter |

Dc |

mm |

21 |

|

|

Branch air duct diameter |

Dn |

mm |

10 |

|

|

Airflow needed to supply the biological filter tank |

Lk |

m3/h |

0.42 |

|

|

Capacity of air blower |

N |

kW |

0.25 |

|

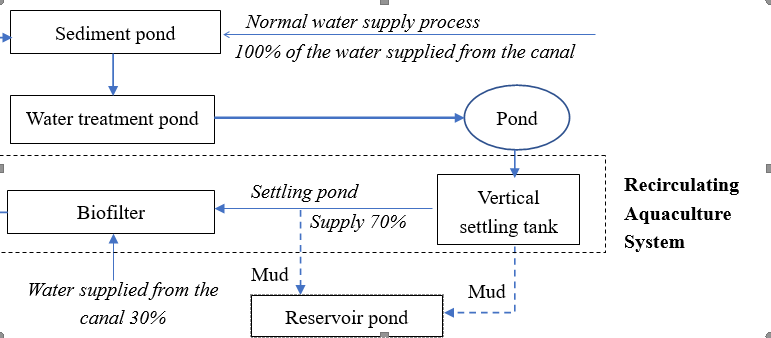

The parameters and layout diagram of the biofilter in the high-density whiteleg shrimp farming model are shown in Figure 3 and Table 3. The model applied in practice uses biological methods with the principle of water circulation based on biological filters. During the model operation, effective microorganisms isolated from high-density whiteleg shrimp pond water were used and instructions on the use of microorganisms in RAS systems were given. In addition, the process of supplying and maintaining microorganisms is provided by the microbiological drip feeder. Microorganisms used are Nitrosomones and Nitrobacter with the density and number of microorganisms used being 106 CFU/ml. The rate is 10 liters/week. The operating process is 30% supplied by the water supply channel and 70% water is pumped from the settling ditch of the mechanical filter. The water mixture is mixed and flowed through the biofilter before entering the settling pond. At the settling pond, the water is pumped back into the channel and circulated back to the biofilter.

Figure 2: Diagram of an experimental model for water circulation treatment for super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming in Vinh Long province

Table 3: The specifications of the biofilter

|

Parameters |

Unit |

Value |

|

Manufacturing materials |

- |

High Density Polyethylene |

|

Size |

mm |

25 x 10 |

|

Surface area |

m2/m3 |

450-550 |

|

Weight |

kg/m3 |

100 |

|

Porosity |

- |

93-96 |

|

Pressure |

bar |

1-3 |

|

Temperature |

oC |

5-55 |

The water used in super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming ponds is first directed to a vertical sedimentation tank. A significant amount of sludge settles at the bottom of a vertical settling tank, allowing clearer water to flow through a settling ditch. Any remaining total suspended solids (TSS) will settle within the settling ditch due to gravity. The clarified water will then be pumped to a biological filter.

A portion of water from the sedimentation tank (70% volume) and water from the canal (30% volume) are combined and sent to the biological filter. In the filter, harmful substances such as total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), nitrite, and other toxins are oxidized and removed while organic matter is broken down. This process also introduces oxygen into the water, which benefits shrimp farming.

After passing through the biological filter, the treated water is returned to the sedimentation pond. From there, the water is circulated back to the canal for 2-3 hours before being cycled back into the shrimp farming ponds. This water treatment regimen ensures that the shrimp farming environment remains healthy and sustainable.

Table 4: Some parameters of super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming ponds were tested

|

Parameters |

Unit |

Value |

|

The water depth of the pond |

m |

1.20 |

|

Pond area |

m2 |

500 |

|

Pond water volume |

m3 |

600 |

|

Daily discharge time |

h |

4 |

|

Water discharge rate from shrimp ponds |

% |

26-30 |

|

Discharge water flow from shrimp ponds |

m3/hour |

44-50 |

Losordo and Hobbs (2000) introduced a technique to determine the recirculation flow rate using mass balance analysis. This involved calculating the flow rate by equating the time derivative to zero for each mass balance and assuming suitable permissible values for the water quality variables. The highest flow rate achieved through mass balances for TAN, DO, and SS is chosen as the desired recirculation flow rate. This flow rate will be calculated using different inputs and assumptions outlined in Table A. TAN, DO, and SS mass balances were conducted using these inputs and assumptions to determine the appropriate recirculating flow rate.

The desired flow rate is calculated using the following formula (Losordo & Hobbs, 2000):

2.3. Theoretical basis

The design of the recirculating aquaculture system is based on the principle of mass balance, in which water quality parameters such as total ammonia nitrogen (TAN), dissolved oxygen (DO), and suspended solids (SS) are maintained within permissible limits. Following the approach of Losordo and Hobbs (2000), the required recirculation flow rate is determined under steady-state conditions, ensuring that pollutant accumulation is minimized. Among the calculated flow rates for TAN, DO, and SS, the highest value is selected as the system design criterion. In this framework, the biofilter plays a central role by converting toxic ammonia into less harmful nitrate, while aeration and mechanical filtration maintain oxygen levels and remove solids. This theoretical basis provides the foundation for sizing biofilters, determining recirculation rates, and ensuring stable water quality in super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming.

3. RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

3.1. Laboratory results

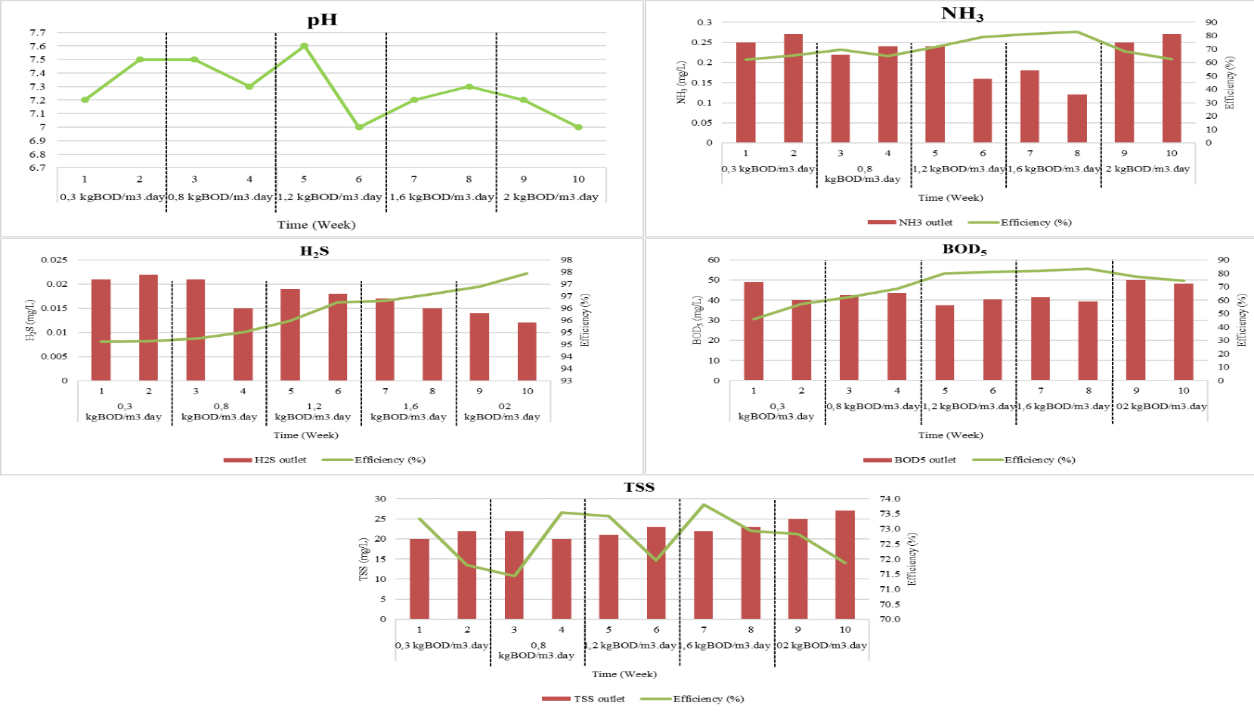

Controlling the pH value is an essential aspect of both wastewater treatment processes and general life. In the context of wastewater treatment, monitoring and regulating pH levels assist in determining whether adjustments to the pH parameters of the input water source are necessary to facilitate the growth and development of microorganisms. It has been observed that microorganisms thrive within a pH range of 6.5 to 8.5, and deviations from this range, be it too high or too low, are detrimental to their growth. The pH value of treated wastewater is illustrated in Figure 4, where fluctuations occur due to temperature and light variations. Despite these unstable fluctuations, the pH level consistently remains within the optimal range for microorganism proliferation.

Ammonia (NH3) is produced as a result of anaerobic decomposition of organic compounds found in the water used for shrimp farming. When formed, NH3 dissolves in water and transforms into the NH4+ ion. Additionally, shrimp release NH3 as a waste product. Consequently, if NH3 is released into the environment at elevated concentrations, it can disrupt the shrimp's osmotic mechanism. The toxic effect of NH3 arises when it diffuses back into the shrimp's bloodstream, causing an increase in blood pH and impairing certain enzymes responsible for eliminating CO2. This change in blood composition interferes with the shrimp's physiological functions and slows down its metabolism. Furthermore, elevated NH3 levels make shrimp more vulnerable to variations in other environmental conditions, including temperature and oxygen levels. Hence, effectively managing NH3 levels is crucial in the overall shrimp farming process.

The concentration of NH3 in the input wastewater ranges from 0.66 to 0.93 mg/l, while the allowable concentration for shrimp to grow normally is only 0.3 mg/l. After a 10-week treatment, the NH3 concentration in the effluent wastewater ranges from 0.12 to 0.27 mg/l, achieving an optimal efficiency of 79% to 83% at an organic load of 1.2 to 1.6 kgBOD/m3.day. Overall, the NH3 concentration meets the requirements for water reuse. When compared to the wastewater treatment of white-legged shrimp farming using a combined biological lake system with cartilaginous seaweed and oysters, the NH3 treatment efficiency in this study reaches 89%, surpassing the aforementioned study. Additionally, the NH3 treatment efficiency is 50-60% higher than the efficiency reported in Shpigel's study (Shpigel et al., 1997).

The treatment efficiency of BOD5 following the biological filtration process is commendable, with a gradual increase leading to high and relatively consistent treatment values. The stability of the biological system's ability to handle wastewater is noteworthy. To thoroughly assess the treatment efficiency of the biological filtration system under consistent input wastewater conditions, a more extended research period is required. This should entail conducting experiments beyond the tenth week for medium and high loads. The resulting graph illustrates the treatment efficiency of BOD in wastewater when subjected to organic loads of 1.2 and 1.6 kgBOD/m3.day reaches an impressive range of 80 to 84%. BOD decomposed by bacteria.

Figure 3: Wastewater treatment efficiency of the biological treatment system (biofilter) through pollution parameters: pH, BOD5, NH3, H2S, TSS in laboratory

Furthermore, it becomes apparent that the output levels drop below 0.05 mg/l following the passage through the biological filtration system, also known as Biofilter. This process effectively treats H2S pollutants, thereby meeting the standards set by QCVN 02-19:2014/BNNPTNT (MARD, 2014).

3.2. Calculating the technical parameters of the biofilter

Accurately estimating water recirculation flow rate and properly sizing nitrifying biofilters are crucial factors in successfully designing any recirculation system. Losordo and Hobbs (2000) propose an approach for sizing biofilters based on nitrification rate. Partial water exchange is used to maintain nitrate-nitrogen concentration in the rearing tank below 20 mg/l, as aquatic animals are susceptible to water quality parameters. A mass balance approach is then used to determine the necessary water flow rate for the recirculating aquaculture system The calculations as proposed (Losordo & Hobbs, 2000) are based on the information and actual data of the high-density white-legged shrimp farming model as shown in Table 5 and actual survey results (Lang Ton et al., 2023). In addition, this information is based on knowledge gained from shrimp farmers' experience. The results of calculating the technical parameters of the biological filter are presented in Table 5.

Table 5: Calculation results of technical parameters of biofilter

|

Parameters |

Value |

Unit |

Data source |

|

Pond size and Biomass |

|||

|

Pond water depth |

1.20 |

m |

Survey results |

|

Pond area |

500 |

m2 |

|

|

Pond volume |

600 |

m3 |

|

|

Maximum culture density |

3.63 |

kg/m3 |

|

|

Shrimp biomass |

2179 |

kg/pond |

|

|

Shrimp farming density |

227 |

con/m2 |

|

|

Shrimp weight |

9600 |

gm/m2 |

|

|

Feed rate as % of body weight |

1.25 |

% |

|

|

Feed rate |

27 |

kg/ day |

|

|

TAN Mass Balance Calculations |

|||

|

Feed protein content |

38% |

|

Real value |

|

Total Ammonia Nitrogen (TAN) production rate |

0.52 |

kg/ day |

Calculated from feed ratio and protein content in feed |

|

% TAN from feed |

0.019 |

% |

Calculated from the ratio of TAN during the farming process to the ratio of feed |

|

Desired TAN concentration in recirculation water |

1.00 |

mg/L |

Average TAN concentration level in shrimp ponds |

|

Passive nitrification |

10 |

% |

Assume the lowest level |

|

TAN available after passive nitrification |

0.47 |

L/ day |

Calculated from the total ratio of TAN for shrimp farming and % passive nitrification |

|

Passive denitrification |

0 |

% |

Assume it doesn't happen |

|

Maximum nitrate concentration desired |

10 |

mg/L |

QCVN 08-MT:2015/BTNMT (column B1) (MORNE, 2015) |

|

New water required maintain nitrate concentration |

46580 |

L/ day |

Calculate the volume of water added to the discharge into the environment |

|

TAN available to Biofilter after effluent removal |

0.42 |

kg/ day |

Calculated from existing TAN and additional TAN |

|

Biofilter efficiency for TAN removal |

50% |

|

Assumed at a low level of 50% |

|

Flow rate to remove TAN to dessired concentration |

838447 |

L/ day |

Calculated from the biofilter's TAN treatment efficiency |

|

|

582 |

L/min |

|

|

Biofilter sizing calculation |

|||

|

Estimated nitrification rate |

45% |

TAN/m2/ day |

Estimated 90% of biofilter efficiency |

|

Active nitrification surface required at rate |

932 |

m2 |

Calculated from the estimated denitrification rate with TAN going to the Biofilter |

|

Surface arrea of media |

300 |

m2/m3 |

Manufacturer's published data |

|

Totoal volume media |

3.11 |

m3 |

Calculated from the required surface area to the surface area/volume ratio of the MBR. |

|

Media depth |

1.08 |

m |

Calculated by 90% of the depth of the pond |

|

Volume/depth yields face area |

2.88 |

m2 |

|

|

Diameter of biofilter |

9.20 |

m |

Actual calculation of fixed biofilter. |

|

Solids Mass Balance Calculation |

|||

|

Estimated percentage of feed becoming solid waste |

25% |

|

Calculated from the rate of leftover food entering the water source |

|

Waste solids produced |

6.81 |

kg/ day |

Calculated from the ratio of food to solids to the volume of food |

|

Desired TSS concentration |

10 |

mg/L |

50% of lowest value QCVN 08-MT:2015 |

|

Estimated % removed by particle trap |

50% |

|

Assuming 50% food decomposition |

|

Waste solids remaining after particle trap |

3.41 |

kg/ day |

Estimated from shrimp culture solids with solids conversion rate |

|

Waste solids remaining solids removal in effluent |

2.94 |

kg/ day |

Calculated from TSS concentration with makeup water flow and biofilter efficiency |

|

Biofilter efficiency |

50% |

|

Estimated value for system efficiency |

|

Flow rate to remove TS to the desired concentration |

587839 |

L/ day |

Calculated from desired TS concentration, biofilter efficiency, and remaining TS |

|

|

408 |

L/min |

|

|

Oxygen Mass Balance Calculations |

|||

|

Submerged filter (1=yes, 0=no) |

0 |

|

The pond does not use wetlands |

|

Oxygen used / kg feed |

30% |

|

|

|

Oxygen used by feed addition |

8.17 |

kg/ day |

|

|

Desired oxygen concentration in the pond |

5.0 |

mg/L |

|

|

Dissolved oxygen concentration supplied to the pond |

18.00 |

mg/L |

|

|

Oxygen used by passive nitrification |

0.24 |

kg/ day |

|

|

Oxygen used for nitrification in biofilter |

0,00 |

kg/ day |

|

|

Total Oxygen used |

8.40 |

kg/ day |

|

|

Estimated flow rate |

646810 |

L/day |

|

|

|

449 |

L/min |

|

|

Calculation of the flow through the Biofilter |

|||

|

Biofilter flow cross-sectional area: Horizontal 3,4m, Depth 1,2m |

4.08 |

m2 |

|

|

Water flow through the section |

0.449 |

m3/min |

|

|

Daily wastewater flow |

164.40 |

m3/day |

|

Thus, the efficiency of the water circulation treatment system in high-density whiteleg shrimp farming ponds is compared to theoretical calculation results, and the actual operating time is guaranteed.

3.3. Operating the model for actual shrimp ponds, reusing 70% of the water

The efficiency of the biological filter in the water circulation treatment system used in high-density whiteleg shrimp farming ponds is highly satisfactory. The biofilter successfully reduces the concentration of pollutants in the water to meet all applicable standards.

Compared to the widely recognized water quality guidelines for shrimp ponds globally, the water quality administered through biological filters within the super-intensive whiteleg shrimp water recirculation system, as evaluated by the fundamental parameters, demonstrates conformity to the standards outlined in Table 6.

Table 6: Results of experimental analysis and operating efficiency

|

Parameters |

Results of experimental analysis |

Efficiency (%) |

|||||

|

Unit |

Sample 1 |

Sample 2 |

Sample 3 |

Sample 4 |

After 02 days |

After 04 days |

|

|

TSS |

mg/L |

43 |

31 |

10 |

12 |

70.0 |

63.3 |

|

DO |

mg/L |

4.40 |

4.70 |

6.9 |

7.2 |

41.7 |

47.9 |

|

NH4+ |

mg/L |

1.55 |

1.23 |

0.035 |

0.044 |

97.5 |

96,7 |

|

NO2- |

mg/L |

0.43 |

0.35 |

< 0.01 |

< 0.01 |

97.1 |

97.1 |

|

H2S |

mg/L |

0.24 |

0.13 |

<0.028 |

< 0.028 |

76.7 |

76.7 |

|

BOD5 |

mg/L |

38 |

29 |

7 |

6 |

78.6 |

82.1 |

|

Alkalinity |

mg/L |

112 |

124 |

117 |

122 |

4.2 |

0.00 |

|

Sample 1: Output water of shrimp pond sedimentation ditch (into biological processor) Sample 2: Water is mixed between canal water (30%) and sedimentation ditch outlet (70%) Sample 3: Output water of biological processor (1st time) - test operation after 02 days. Sample 4: Output water of biological processor (2nd time) - test operation after 04 days. |

|||||||

3.3. Pollutant removal efficiency

To evaluate the effectiveness of pollutant removal in water sources supplied to shrimp ponds, water samples at 3 different locations in 2 experimental shrimp farming periods were taken for testing, and the results are presented in Table 7. The results showed that the biofilter in the shrimp pond water circulation treatment system did not affect the concentration of dissolved solids, total alkalinity, and salinity of shrimp pond water. Therefore, when the concentration of these parameters changes from canal water, it is necessary to add minerals to balance the water.

For H2S, the removal efficiency of the biofilter is quite high. With this efficiency, the concentration of H2S in the water after being treated and put into the settling pond is very low. Nutrient pollutants arising from shrimp waste (ammonia, nitrite) are also removed with quite high efficiency. Both of these parameters are quickly converted into nitrate (N-NO3, not toxic to shrimp) thanks to the microorganism system and the biofilter. Thanks to the gas supply at the biofilter, the efficiency of removing organic matter is quite good through the increase in dissolved oxygen concentration in the outlet water. Calculation results show that the efficiency of increasing the average dissolved oxygen concentration is up to 70-75%. In addition, the results also showed that the total hardness and total control removal efficiency of the high-density whiteleg shrimp pond water circulation system was low on average. The factor that caused this reduction was the efficiency of the system in removing the maximum carbon dioxide in the shrimp pond water.

Table 7: Summary of results of evaluating the pollutant removal efficiency of biofilters in high-density whiteleg shrimp pond water circulation systems

|

Parameters |

Unit |

Shrimp farming 1 |

Shrimp farming 2 |

||||

|

|

SF1 |

SF2 |

SF3 |

SF1 |

SF2 |

SF3 |

|

|

pH |

- |

7.6 |

7.4 |

7.7 |

7.65 |

7.72 |

7.62 |

|

Carbon dioxide |

mg/l |

2.31 |

2.45 |

1.15 |

2.31 |

2.47 |

0.95 |

|

Total of the hardness |

mgCaCO3/l |

120 |

118 |

95 |

121 |

115 |

87 |

|

Total of the alkalinity |

mgCaCO3/l |

111 |

104 |

84 |

116 |

101 |

89 |

|

Ammonia |

mg/l |

0.248 |

1.920 |

0.034 |

0.542 |

1.936 |

0.028 |

|

Nitrite |

mg/l |

0.595 |

0.663 |

0.015 |

1.109 |

1.180 |

0.013 |

|

Salinity |

‰ |

0.115 |

0.111 |

0.091 |

0.110 |

0.105 |

0.084 |

|

DO |

mgO2/l |

4.19 |

4.11 |

7.27 |

4.44 |

4.17 |

7.39 |

|

Hydrogen sulfide |

mg/l |

0.484 |

0.432 |

0.010 |

0.343 |

0.571 |

0.010 |

|

SF1: Canal water sample SF2: Water sample after gravity settling into the biofilter SF3: Water sample after water circulation system into settling pond |

|||||||

3.3. Discussion

Concentrations of pollutants in super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming pond water are low and meet QCVN 02-19:2014/BNNPTNT for whiteleg shrimp farming water quality. The dissolved oxygen concentration is very high, suitable for shrimp farming, and the concentration is much higher than the limit value prescribed by QCVN 02-19:2014/BNNPTNT. Toxic ions such as TAN and nitrite all have very low concentrations and meet corresponding regulations.

The operational efficiency of the biofilter is highly effective when treating a mixture of 30% canal water and 70% shrimp pond water, which has undergone gravity settling by extracting 70% from the pond settling process. The most significant reductions in concentration were observed for ammonia and nitrite, with the effluent experiencing a reduction ranging from 96.7% to 97.5% for ammonia. This indicates a considerable level of efficiency achieved through a combination of mechanical sedimentation and biological treatment. Besides, the water circulation treatment demonstrates a high level of efficiency when it comes to reducing total suspended solids (TSS) and biological oxygen demand (BOD5), with percentage reductions of 63-82%. This highlights the effective filtration of suspended substances by the biological filter in addition to its ability to remove toxins from the water of super-intensive whiteleg shrimp ponds.

Moreover, the survival of white shrimp was not adversely affected by the presence of any toxic substances such as nitrite and sulfide. This suggests that the effectiveness of microflora and oxygen supply plays a key role in promoting the shrimp's well-being. Consequently, the circulatory water treatment system employed in super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming ponds has a negligible impact on the amount of dissolved solids present in the water environment. Consequently, to maintain optimal alkalinity in the water used for whiteleg shrimp farming it is still necessary to perform the water balance step. The laboratory test results have determined that the experimental model holds great promise. These results have been practically implemented on a large scale for real super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming, specifically in ponds covering an area of 500m2.

Economically this model can help reduce the cost of operating and managing shrimp ponds. By reusing water during shrimp farming, this model reduces water consumption and helps save costs on water treatment and wastewater treatment. In addition, high technology in wastewater treatment also helps remove pollutants and create a better pond environment; helping shrimp grow better and improve product quality. Save up to 70% of the cost of chemicals and antibiotics for treating water supplied to shrimp ponds. According to the survey results, using a water circulation system for super-intensive white-leg shrimp farming will save about 40% of the cost of energy (electricity, oil) to pump water from the canal into the preliminary settling pond (accounting for 70% of the amount of water needed to be added). The productivity of white-leg shrimp using water treated by a water circulation system for super-intensive white-leg shrimp farming has increased by about 15%. Soon, this result will be initially applied to large-scale super-intensive shrimp farming in three coastal districts: Binh Dai, Thanh Phu, and Ba Tri of Ben Tre province.

4. CONCLUSION

The laboratory test results have determined that the experimental model holds great promise. These results have been practically implemented on a large scale for real super-intensive whiteleg shrimp farming, specifically in ponds covering an area of 500m2. The effectiveness of the treatment process has been impressive, ensuring that the water supplied to these ponds adheres to the quality standards outlined in QCVN 02-19:2014/BNNPTNT. Although the results of calculating the technical parameters for the biofilter in the total water circulation system for high-density whiteleg shrimp farming cannot be considered a highly complete model for immediate use, it needs to be applied in practice to determine experimental errors. However, the results of this study showed that the biofilter system in RAS for super-intensive whiteleg shrimp pond water has shown promising results in terms of treatment efficiency, establishing its practical feasibility for wide application.

Acknowledgments: The paper was prepared with the financial support of the project in the Department of Science and Technology of Vinh Long province “Research on developing wastewater treatment process for super-intensive shrimp ponds with circulating water in Vinh Long province”.

Tôn Thất Lãng1*, Lê Thị Ngọc Diễm 1, Nguyễn Thị Thu Hiền1,Trần Thị Kim Tú2

1Ho Chi Minh University of Natural Resources and Environment, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam;

2Center of Environment and Technology Service, Ho Chi Minh City, Vietnam.

(Source: The article was published on the Environment Magazine by English No. IV/2025)

REFERENCES

1. Boyd, C. E., Davis, R. P., & McNevin, A. A. (2022). Perspectives on the mangrove conundrum, land use, and benefits of yield intensification in farmed shrimp production: A review. In Journal of the World Aquaculture Society (Vol. 53, Issue 1, pp. 8–46). John Wiley and Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12841.

2. Emerenciano, M. G. C., Rombenso, A. N., Vieira, F. D. N., Martins, M. A., Coman, G. J., Truong, H. H., Noble, T. H., & Simon, C. J. (2022). Intensification of Penaeid Shrimp Culture: An Applied Review of Advances in Production Systems, Nutrition and Breeding. In Animals (Vol. 12, Issue 3). MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/ani12030236.

3. Krummenauer, D., Peixoto, S., Cavalli, R. O., Poersch, L. H., & Wasielesky, W. (2011). Superintensive Culture of White Shrimp, Litopenaeus vannamei, in a Biofloc Technology System in Southern Brazil at Different Stocking Densities. In JOURNAL OF THE WORLD AQUACULTURE SOCIETY (Vol. 42, Issue 5).

4. Lang Ton, T., Tan Lam, V., Thi Kim Tu, T., & Tuan Nguyen, V. (2023). Evaluation of the current status of wastewater management and treatment from super-intensive whiteleg (Penaeus vannamei) shrimp ponds in Ben Tre Province. Vietnam Journal of Hydrometeorology, 3(16), 56–64. https://doi.org/10.36335/vnjhm.2023(16).56-64.

5. Losordo, T. M., & Hobbs, A. O. (2000). Using computer spreadsheets for water flow and biofilter sizing in recirculating aquaculture production systems. In Aquacultural Engineering (Vol. 23). www.elsevier.nl/locate/aqua-online.

6. MARD (Ministry of Agriculture and Rural Development). (2014). QCVN 02 – 19: 2014/BNNPTNT. National technical regulation - On brackish water shrimp culture farm - Conditions for veterinary hygiene, environmental protection and food safety.

7. MONRE (Ministry of Natural Resources and Environment). (2015). QCVN 08-MT: 2015/BNNPTNT. National technical regulation on groundwater quality.

8. Nguyen, T. A. T., Nguyen, K. A. T., & Jolly, C. (2019). Is super-intensification the solution to shrimp production and export sustainability? In Sustainability (Switzerland) (Vol. 11, Issue 19). MDPI. https://doi.org/10.3390/su11195277.

9. Nugraha, M. A. R., Dewi, N. R., Awaluddin, M., Widodo, A., Sumon, M. A. A., Jamal, M. T., & Santanumurti, M. B. (2023). Recirculating Aquaculture System (RAS) towards emerging whiteleg shrimp (Penaeus vannamei) aquaculture. In International Aquatic Research (Vol. 15, Issue 1, pp. 1–14). Islamic Azad University of Tonekabon. https://doi.org/10.22034/IAR.2023.1973316.1361.

10. Shpigel, M., Gasith, A., & Kimmel, E. (1997). A biomechanical filter for treating fish-pond effluents. Aquaculture, 152(1), 103–117. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1016/S0044-8486(97)00004-5.

11. Thi, N., & Lan, P. (2013). Social and ecological challenges of market-oriented shrimp farming in Vietnam. 12. http://www.springerplus.com/content/2/1/675.

12. Villarreal, H., & Juarez, L. (2022). Super-intensive shrimp culture: Analysis and future challenges. In Journal of the World Aquaculture Society (Vol. 53, Issue 5, pp. 928–932). John Wiley and Sons Inc. https://doi.org/10.1111/jwas.12929.